Nomura: Bank of England to Raise Rates Once Every Six Months

Past cycles show the Bank of England (BOE) usually raises interest rates much more frequently than the market expects, according to research by Nomura, which could mean a stronger Pound going forward.

The Bank of England could raise interest rates every six months from November, according to research from Japanese lender Nomura, which means the base rate could go as high as 1.5% before the end of 2019.

BoE rate setters will likely hike in increments of 25 basis points until late 2019 when they are expected to slow the pace of rate increases from two per year to one every nine months.

Bank rate will reach a peak of 2.5% around five years from now, it’s terminal rate, Nomura’s bond research team says.

This means short term “market rates” will rise over the coming years, which is good for Sterling, although the bond analysts make no forecast for just where the Pound might go.

Wednesday’s call from Nomura represents an upgrade from the bank’s previous forecast for the BoE to hike rates once every nine months, beginning in December.

Their projections are also way above market forecasts which currently suggest that, after an initial move by the BoE in November, UK interest rates will rise once every five quarters.

History Lesson: BoE Moves Faster Than Many Expect

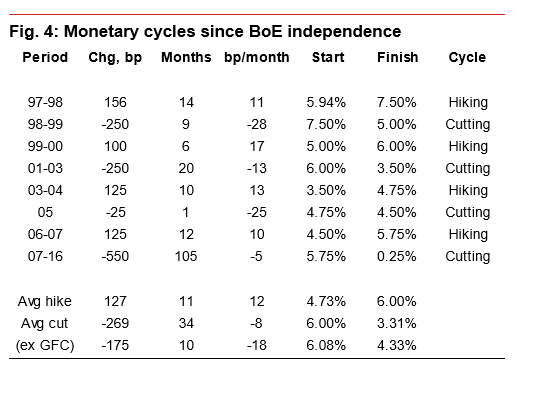

Nomura’s analysis of past interest rate cycles shows the Bank of England has typically raised rates by somewhere between 100 basis points and 150 basis points every year once it has started to move.

This is a much faster pace than is implied by even Nomura’s latest forecasts, which are ahead of the market, but the difference accounts for the fact that the world has changed considerably since the last time the BoE entered a hiking cycle.

"Relative to post-BoE-independence tightening phases, this would still constitute a “gradual” and “limited” hiking cycle, despite being faster than the market is currently expecting," says George Buckley, Nomura's European Economic Research Analyst.

The Bank of England has gone to great lengths to emphasise in its communication over the years that any eventual interest rate hikes will be “gradual and limited”.

It has also said that the long run upper and lower levels of the bank rate are likely to be lower than they were before the financial crisis.

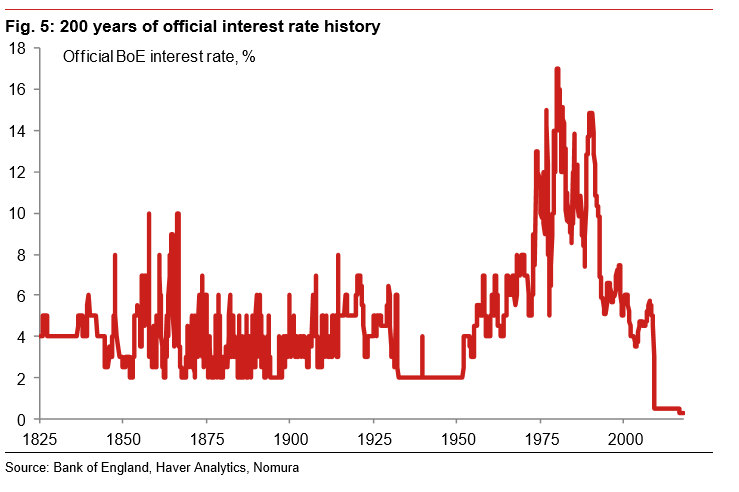

Buckley notes that not only do Nomura’s forecasts imply a slower pace of hiking than before, they also imply the bank rate will find its ceiling at 2.5%, which is a long way below the average 4.65% bank rate of the last 200 years.

"If we based our forecasts for official interest rates on past history alone, along with the MPC’s recent commentary and guidance, we would be forgiven for expecting a relatively short hiking cycle of 100bp or less in 25bp increments, taking quite some time thereafter to reach a level lower than its historical average (4-4.5% in nominal terms)," Buckley writes, in a note.

Accounting For The New Normal

Buckley notes the flaws inherent in looking simply at the past in an effort to predict the future.

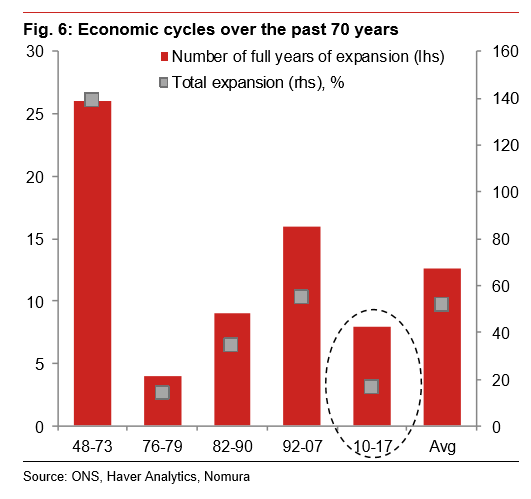

"It is questionable, however, how useful such historical comparisons are. After all, they are based on a very short period of history, when interest rates were cut more than they were raised – a period which the previous Governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King described as the NICE (Non-Inflationary Consistently Expansionary) decade," Buckley writes.

A less backward-looking analysis would take into account the current forces keeping rates low, such as economic fears linked to Brexit and concerns over slow growth.

In analysing current and likely future conditions, forecasters and policymakers alike should look at how long the current economic growth cycle has left to run and the impact that Brexit could have on expectations for the economy and growth.

"If we assume a two-year transition period for Brexit between 2019 and 2021 and a comprehensive “Canada-plus” style deal in place from 2021 onwards, then it seems entirely reasonable that we should be forecasting a continuation of the economic expansion for the UK over the next few years," says Buckley.

These assumptions are the basis for Nomura’s rate hike projections. Buckley and his team have grounds for their assumptions because the BoE has said a rate hike will only happen if it believes the economy will continue to perform in the way that it has done.

“All MPC members continue to judge that, if the economy follows a path broadly consistent with the August Inflation Report central projection, then monetary policy could need to be tightened to a somewhat greater extent over the forecast period than current market expectations,” the BoE says, in its September monetary policy statement.

Bond Interest Rates To Rise

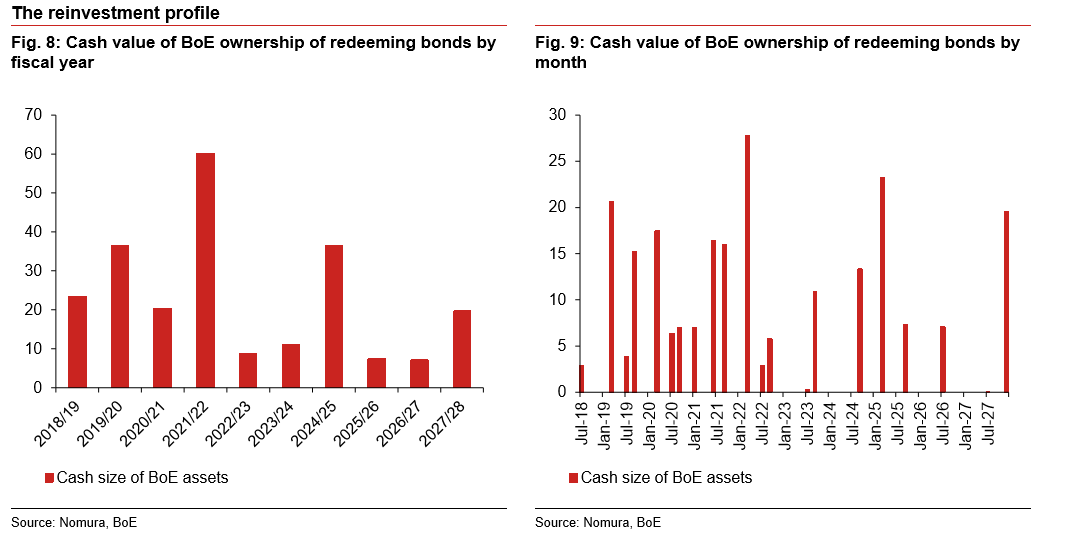

A rising base rate will always market interest rates, and also savings rates, higher. However, there could be additional upward pressure on these rates over the years to come due to an eventual winding down of the BoE’s quantitative easing (bond buying) program.

The Bank of England currently owns around £435 billion of government bonds. It has been a large buyer in the bond market ever since the financial crisis, returning periodically to reinvest monies gained through maturities, or to increase its holdings at times when the scale of the QE program has been increased.

Bond “yields” do the opposite to bond prices. When there is demand in the market the prices of bonds will rise and this pushes down the yield. When demand falls out of the market bond prices will fall, and this pushes up yields.

Eventually the Bank of England will make the decision to stop reinvesting the money it gets from maturing government bonds. This will mean a significant source of demand falls out of the market, pushing up yields.

“A little over half of the APF’s £435bn rolls off between FY 2018/19 and the FY 2027/28,” says Buckley. “Whether one looks on a monthly basis or even aggregates up to fiscal year basis, the point is the profile is extremely “lumpy”.”

The BOE's reinvestment programme has contributed a major tranche of demand for government bonds, as much as one third of market demand in some different maturity segments. Buckley forecasts that an eventual exit of the BoE from the UK government bond market will hit 7-15 year (mid-term) maturity segment, prompting a sharp fall in bond prices and an uplift in yields.