UK Bond Yield Jumps in Fresh Blow to Reeves

- Written by: Gary Howes

Chancellor Rachel Reeves leaves No 11 Downing Street to deliver her Spring Statement. Picture by Alecsandra Dragoi / Treasury

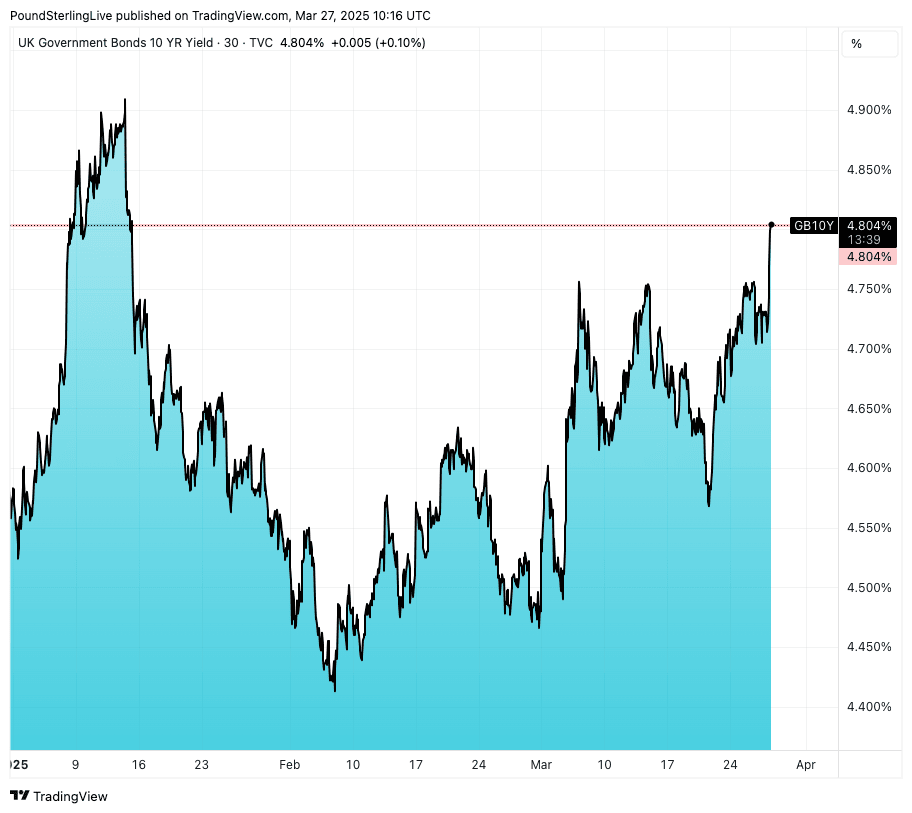

The ten-year UK bond yield - the UK's borrowing benchmark - is rising again on Thursday, just hours after Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced her Spring Statement.

The yield reached 4.80% on Thursday morning, putting it at its highest level since January 15.

It was in early January that yields spiked amidst a bond market wobble linked to fears about the UK growth trajectory.

Bond markets are where the government borrows money from investors who ultimately fund the government's deficits. The rising yield signals a demand for increasing levels of compensation for taking on UK sovereign debt.

The ten-year yield helps determine the cost of money for homebuyers and the biggest UK companies, meaning the cost of borrowing in the economy is at risk of rising further.

Above: GB ten-year bond yield.

It also signals the government's own debt repayments to lenders are increasing, which will only diminish the Treasury's headroom.

Bond investors will remain nervous about the UK's debt trajectory as the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) said the annual debt interest spending bill will exceed £100 billion every year until 2030.

The OBR nevertheless said the Chancellor will meet her fiscal rules that require public debt as a percentage of GDP to be falling by the fifth year of the forecast.

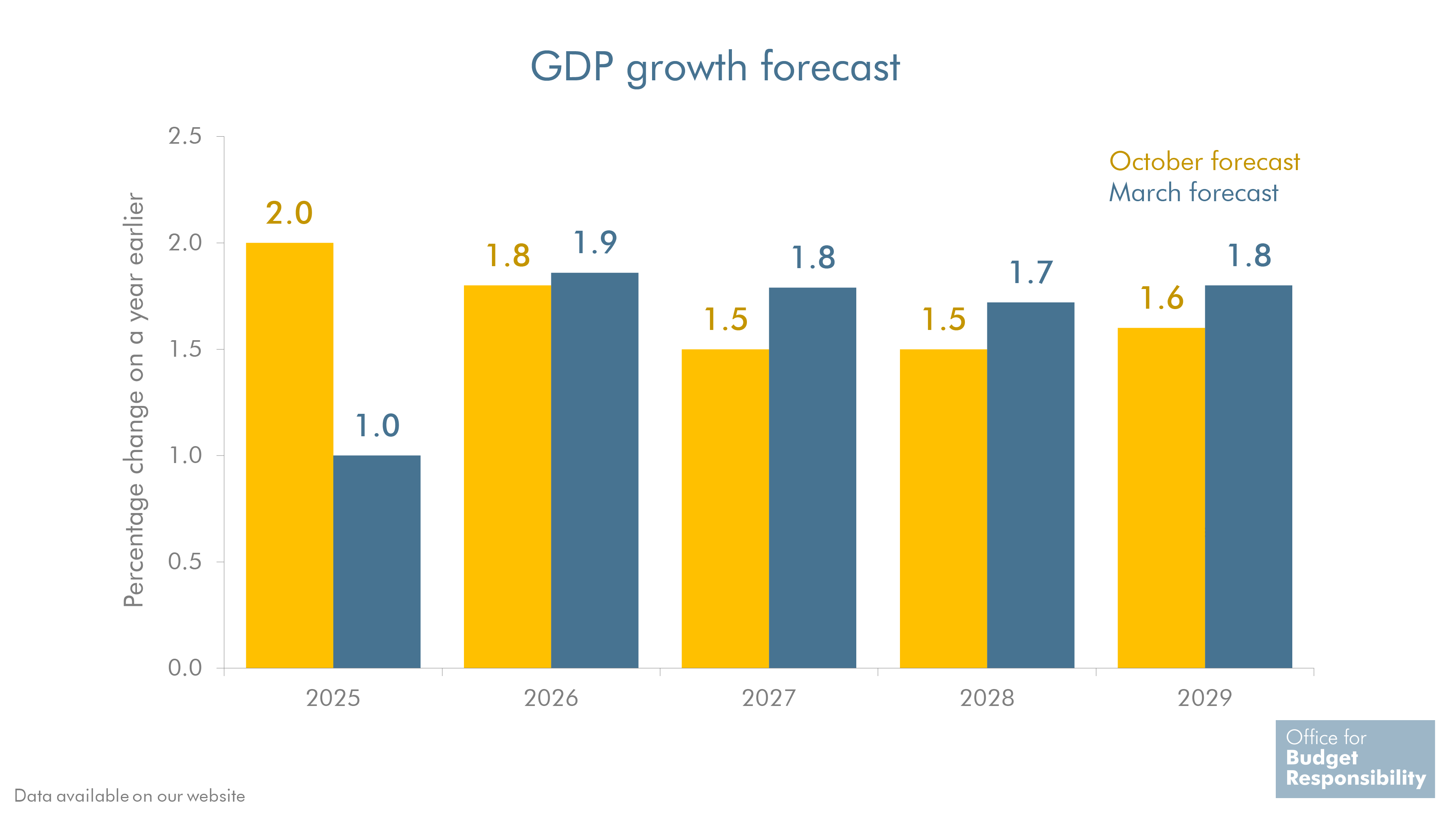

However, that prediction is based on a precarious assumption that the economy will grow at rates in excess of 1.5% in the coming years.

The OBR also slashed the 2025 growth forecast in half to 0.5%. This represents a big forecasting error: if the OBR is unable to forecast five months in advance, how can it forecast two, three and five years ahead?

"In today’s media coverage of the Spring Statement, no-one is asking the crucial question: If the OBR has made such a hash of forecasting this year’s GDP growth, why should we believe any of their revised forecasts - for this year and the next 4 years?" queries Andrew Sentance, an economist and former member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee.

This is a question lenders will be asking, and doubts are being printed in the rising bond yields we are seeing.

"I'm not sure that the political commentators realise quite how badly this budget is going to unravel. Unless I'm badly wrong (which I have been before but normally am not), the moment it appears that growth is running way below 2%, we are close to IMF territory," says Douglas McWilliams, the founder of Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR).

Investors lend to the government over multi-year timeframes on the understanding that economic growth ultimately guarantees their debts.

When growth disappoints, tax revenues ultimately undershoot, meaning more money must be borrowed to cover the shortfall.

The risk is that the government then swamps debt markets with new debt, which invariably sees investors demanding higher interest rates, further piling costs onto the government.