Macron is "No Saviour" says Commerzbank’s Weil

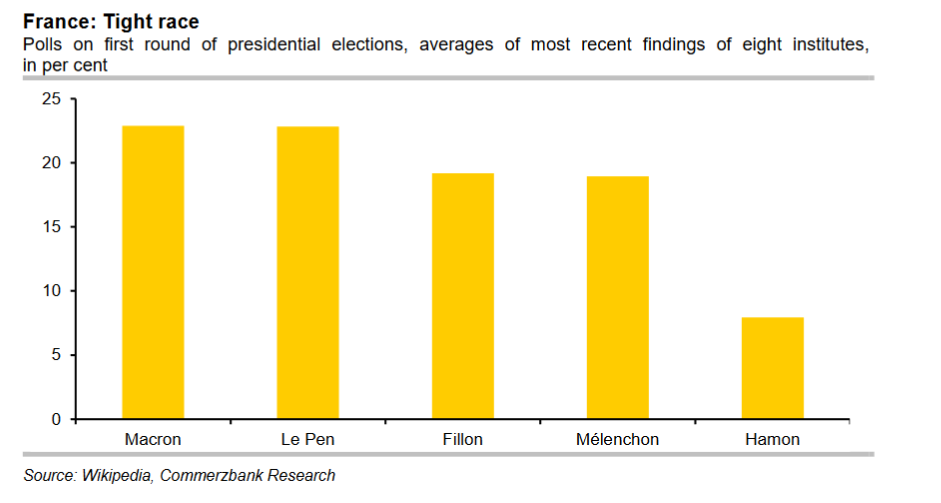

The current favourite in the four-horse race that is the French presidential election is Emmanuel Macron.

We know he is favoured by the markets with the Euro likely to rise in the event of him winning.

It is undoubted that a Macron win would be the ideal outcome for financial markets and would strengthen the Euro, as it would erase the risk of France leaving the EU but once 'enthroned' how will markets rate his policy agenda – will they give it the thumbs up or the thumbs down?

Economist Christoph Weil at Commerzbank cautions not to expect anything spectacular from Macron, and he takes pains to make it clear that - if nothing else - Macron is a creature of Hollande.

He is in Hollande’s cabinet – as his minister for the Economy - and has therefore been the architect of many of the existing reforms implemented in an attempt to pull France out of the sleepwalk it fell into following the crisis.

However, it is this legacy which makes Weil sceptical that he has the dynamism and wherewithal to really deal a death blow to some of France’s most pressing problems.

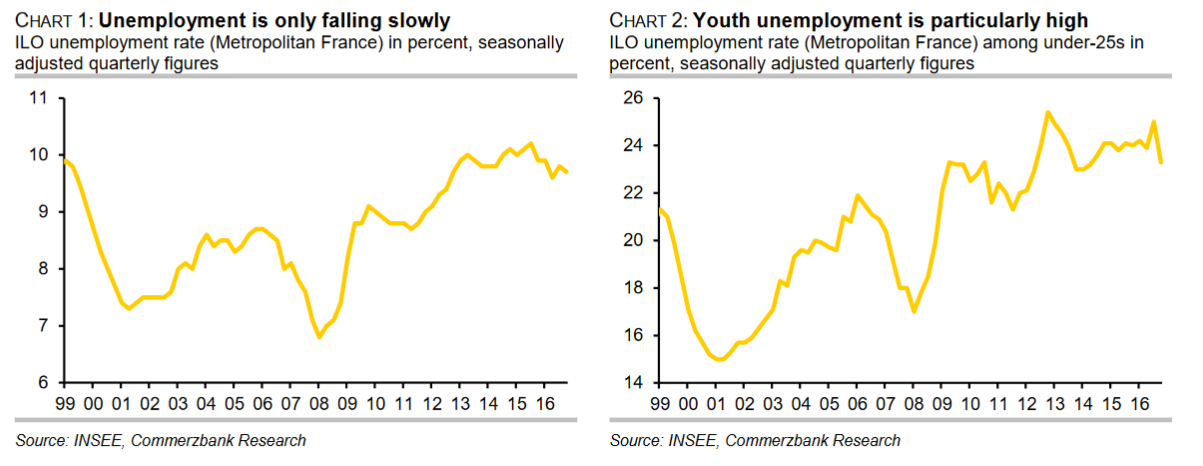

The main one is the country's high unemployment rate, which stands at 9.7% and 23% for youths.

Unfortunately, Weil does not think the plans already put in place by Macron under Hollande will be effective enough.

“Compared to the mainly protectionist approaches taken by candidates from the extreme left and right, his plans would be a far better response to the current economic problems facing France. However, it is doubtful whether they would significantly alleviate them,” says Weil in a note dated April 22.

One major policy to beat unemployment is through reform of Unemployment Insurance which Macon wants to remove as a burden for employers to bear and instead support jobseekers with benefits payed directly out of taxes.

A further measure is to lower corporation tax from 33.3% to 25.0%.

A third measure is to introduce greater flexibility into how employers and employees agree pay and conditions. He wants allow diversification away from the straight jacket of block agreements between management and unions.

Macron wants to increase incentives for the unemployed to return to or seek work. One idea is an ‘activity premium’ which gives a worker an extra month of pay in the year if they find a job.

Finally, he wishes to increase investment by 50bn euros.

Some of these policies have already been implemented such as reduction in employer’s tax burden but have not yet appeared to have borne fruit, although Weil says this is because it is still too new having only been introduced last autumn.

Weil is also sceptical of the success of the proposals for increased flexibility in discussing employment terms.

France does not enjoy the close working relationship between workers and bosses that has supported Germany, and the enmity is likely to stifle progress in this area.

Another weakness of the reform is that any new agreements or amendments to existing agreements made between employees and employers must also be ratified by employee representatives, who could, simply stubbornly reject them out of hand.

“Also, deviations from collective agreements require the consent of employee representatives, which has so far proved a very difficult hurdle to overcome given the lack of cooperation between employers and trade unions in France (unlike in Germany), for example,” said Weil.

The same rights to veto have not been awarded to employee representatives in Spain, for example, where similar reforms have been made recently.

No Teeth

The main problem with is policies for incentivising the unemployed back to work is a similar lack of teeth.

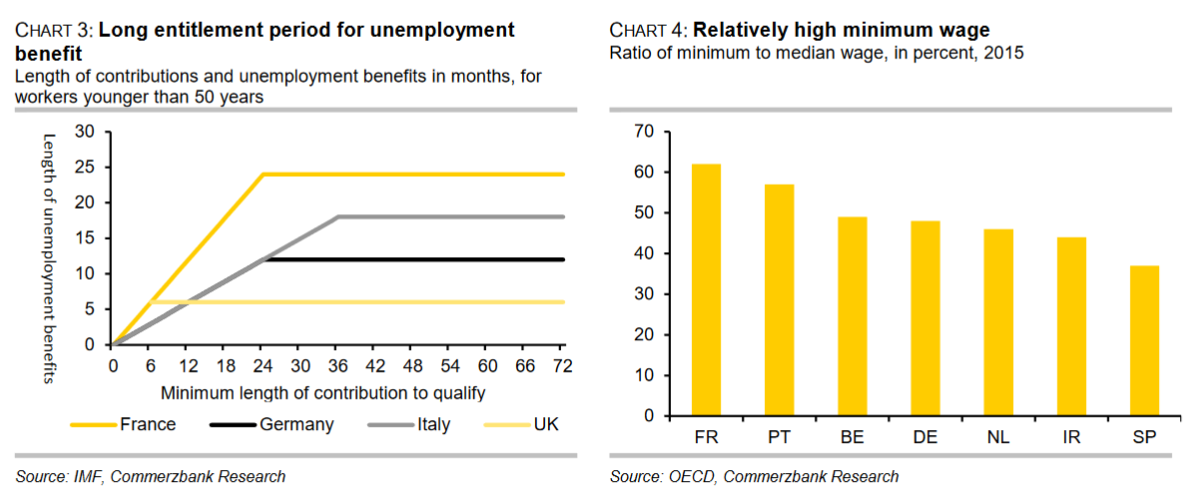

He is not willing to cut the 24-month period that French unemployed are allowed to draw benefits even though it is higher than most other countries in the Eurozone.

In addition the minimum period of time one need work before being able to draw jobseekers is also pitifully short.

Nor does he want to change the law limiting the working week to 35-hours, or to cut the minimum wage, which is the highest in the EU relative to the median wage (at 60%).

It is only in the sphere of corporation tax where Macron is willing to go further than Hollande by cutting taxes generously.

He also wants to cap healthcare spending at 2.3% of the budget.

Finally he wishes to cut down the size of the civil service.

The main problems Macron faces, however, are purely political and come from the fact he will probably have very little support from the lower house of reps.

“Macron is unlikely to receive the support of a majority in parliament. In the legislative elections to be held in June, the established parties should win a majority between them. The socialists will certainly not back his labour market reforms or his proposals for cuts in public spending, nor will the conservative camp grant him unconditional support, especially when it comes to capping increases in health expenditure. Here, like all his predecessors, he can expect strong resistance from all parties concerned. The same applies to job cuts in the public sector,” says Weil.

The prospect of a lame duck president may therefore render the debate pointless in the end, especially given what has happened to Donald Trump who does have a majority and yet still cannot get his policies through.

In relation to European politics he may also face much opposition, especially from France’s key ally in the club Germany.

Macro’s motto is “the strong should help the weak,” and at a European level that involves sharing the reasonability more evenly for the weak periphery, however, these policies have so far brought him into direct conflict with Germany who is opposed to that sort of altruism.

Could France be about to receive a lame-duck president?