Rising Term Premium the Main Culprit Behind Long-term Bond Yield Rally

- Written by: Gary Howes

Image © Adobe Images

The rise in longer-term bond yields is widely credited for recent market jitters and a rise in the Dollar.

But what is causing this rise, and can it continue? Of course, the answer would offer some clues into how much further the Dollar rally can extend from here.

The regular assumption is that bond yields are rising because investors anticipate inflation to remain at higher levels than was the case in the post-financial crisis era, which means a higher interest rate environment.

This lowers the value of longer-term bonds as investors fear inflation will eat away their value and raise their yield. But this environment has been well understood for some time now and alone doesn't explain the market-jolting spike in yields we have seen over the course of the past two weeks.

Instead, a number of economists are pointing the figure at one key determinant of bond value: the risk or term premium.

"The case for higher long yields is real. Various models point to the risk or term premium in longer bond yield still being quite depressed after years of sizable central bank bond purchases. As these bond holdings are now being unwound and this process coincides with huge government deficits and high public debt, meaning a lot of bond issuance, one should expect the risk premium to rise as well," says Jan von Gerich, Chief Analyst at Nordea Bank.

The Federal Reserve of New York explains that yields on bonds are composed of two components: expectations of the future path of short-term yields and the term premium:

"The term premium is defined as the compensation that investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond. Since the term premium is not directly observable, it must be estimated, most often from financial and macroeconomic variables."

Economist Albert Edwards at Société Générale describes term premium as "compensation for the uncertainty of holding longer maturities – especially in the face of fiscal dysentery."

He points out that both Bloomberg's John Authers and Robert Armstrong at the Financial Times concur that it is not the real economy or inflation data that is driving this latest yield rally, rather it is increasing uncertainty that is driving up the term premium.

"Never in my career have I witnessed such uncertainty about where we are in the economic cycle. Is that long-promised recession still lurking around the corner or are we at the start of a new economic cycle? Many investors are apparently increasingly convinced it’s the latter," says Edwards.

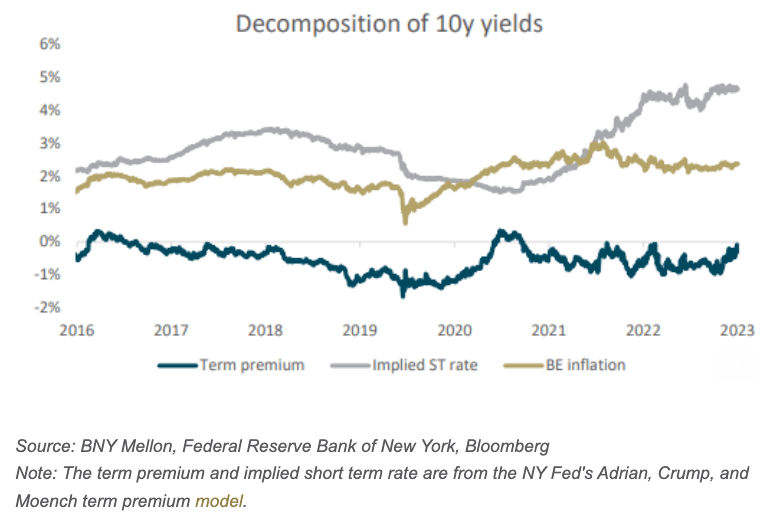

The above comes courtesy of BNY Mellon where analyst John Velis describes a chart showing a widely followed estimate of the 10-year Treasury term premium, or the extra compensation required to hold a long-term bond (blue line).

It also shows a related estimate of the market’s expectation for short-term policy rates in ten years’ time (grey line).

"Both the term premium and the estimated policy rate have moved significantly higher in recent months. The former, which had been negative and falling for most of the post-GFC/pre-pandemic period, is now nearly positive," says Velis.

The move lower in the term premium during the decade before the pandemic reflects the impact of central bank purchases of bonds during the post-Great Financial Crash era dominated by central bank quantitative easing (which ultimately created the demand to quash bond yields).

"Furthermore, a prevalent belief in 'secular stagnation' after the GFC implied lower equilibrium interest rates and hence bond yields. Those days are now behind as we move forward in the post-COVID world," says Velis. "The bottom line is that term premia are returning to more reasonable levels and expected short rates to much higher values."

The rise is therefore likely to hold as a process of normalisation plays out.

Nevertheless, Nordea Bank's von Gerich thinks that the peak in this rate rally is close.

"The US economy is likely to cool gradually and inflation pressures to recede, which is not usually an environment of rising bond yields. As a result, while further near-term increases in bond yields can certainly not be excluded, we think we are already close to the cycle highs in yields, and rather see US 10-year yields trade closer to 4.5% than 5% in the coming months," he says in a new note.

The economist also points out that higher yields are not taking place in a vacuum, and there are feedback loops in place that speak against at least a further rapid rise in interest rates.

"The faster yields rise, the bigger the negative impact on the economy and risk appetite. The equity market has already been under pressure, as yields have risen, and a further rise could easily lead to a bigger fall in equity prices. Such a drop, in turn, would likely ignite flight-to-safety demand for bonds, thus at least stopping but likely also reversing some of the earlier rises in yields," says von Gerich.

When these longer-term yields stop rising, calling the end of the Dollar rally becomes easier.