Bank of England Bank Rate "Could Well Have to Rise Further," Says MPC's Cunliffe

- Written by: James Skinner

"So while I expect interest rates having risen back to above pre-pandemic levels, not to see again the levels we saw over the last 12-months, I also don't think we're heading back to the interest rates of the 1990s," - BoE Deputy Governor John Cunliffe.

Image © Adobe Stock

The Bank of England (BoE) could well need to lift interest rates further in the months ahead, a member of the Monetary Policy Committee has said, in order to ensure that a near double-digit inflation rate eventually returns to the coveted target of two percent over the medium-term.

BoE interest rate policy has been a source of consternation for many within and around the markets during recent months.

This has led Pound Sterling into the crosshairs of speculative short sellers who've recently built up their largest wager against the British currency since 2019 and before the UK's entry into the Brexit transition period.

But for those who missed the BoE's other communications, some further insight was offered by Deputy Governor John Cunliffe on Wednesday.

"Now they're above pre-pandemic levels and now of course we have to ensure that the inflation we're seeing in the economy - I think most of which but not all is coming from shocks that people understand are from abroad - that that doesn't become established in the economy. That inflation doesn't become the new normal. So interest rates may well have to rise further," he told ITV's Joel Hills.

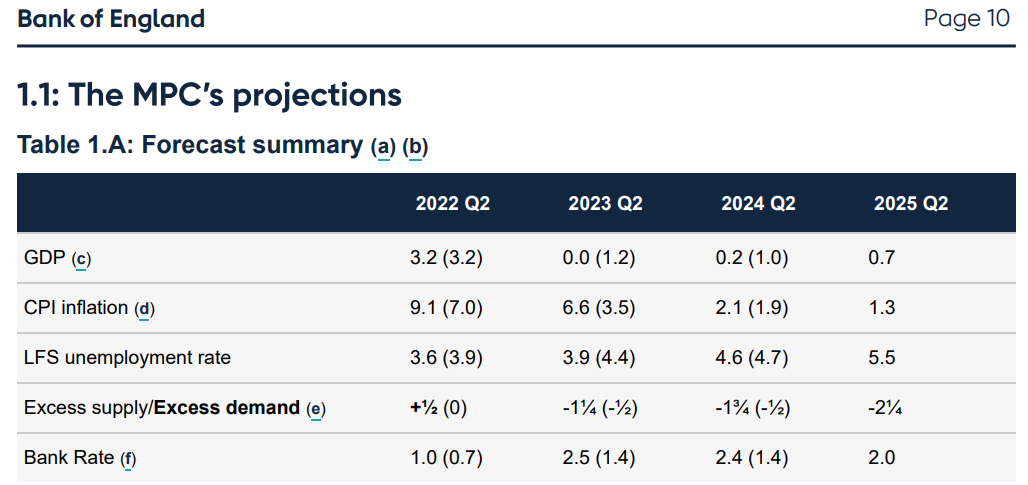

Above: UK inflation and Bank of England forecasts. Source: May Monetary Policy Report. Click for closer inspection.

"But there are also some features about interest rates that are very different now to where they were 15 or 20 years ago and it's about the balance of savings Vs investment in the economy," Cunliffe said.

"So while I expect interest rates having risen back to above pre-pandemic levels, not to see again the levels we saw over the last 12-months, I also don't think we're heading back to the interest rates of the 1990s," he added.

The Bank of England raised its Bank Rate in May for what was a fourth time since before the onset of the pandemic, lifting the benchmark to 1% and its highest level since before the 2008 financial crisis.

But the Pound fell following the decision after the BoE suggested using its economic forecasts that inflation would be likely to fall back to a level that is materially below the coveted 2% target in future years if it delivered upon financial market expectations for its interest rate in the months ahead.

Above: May Monetary Policy Report forecasts. Source: Bank of England. Click image for closer inspection.

GBP to USD Transfer Savings Calculator

How much are you sending from pounds to dollars?

Your potential USD savings on this GBP transfer:

$1,702

By using specialist providers vs high street banks

The idea is that the erosion of household spending power due to increased prices of energy, food and other costs will sap demand from the economy.

This would eventually force economic growth as well as many other prices across the economy to fall.

“We are now walking a very fine line between tackling inflation and the output effects of the real income shock and the risk that that could create a recession,” BoE Governor Andrew Bailey said from Washington in April.

"The challenge, of course, is that on the other side of the path, is where inflation currently is. But, more particularly, the risks as we see them going forwards, and I would highlight as we say in the minutes actually, in the statement, that the risks are, if anything, on the upside, we think for inflation, going forwards," he qualified in caveat during the May Monetary Policy Report press conference.

Markets have bet heavily in recent months that Bank Rate could rise to 2% by year-end and the BoE has signalled repeatedly, using its economic forecasts, that such an outcome may be unlikely.

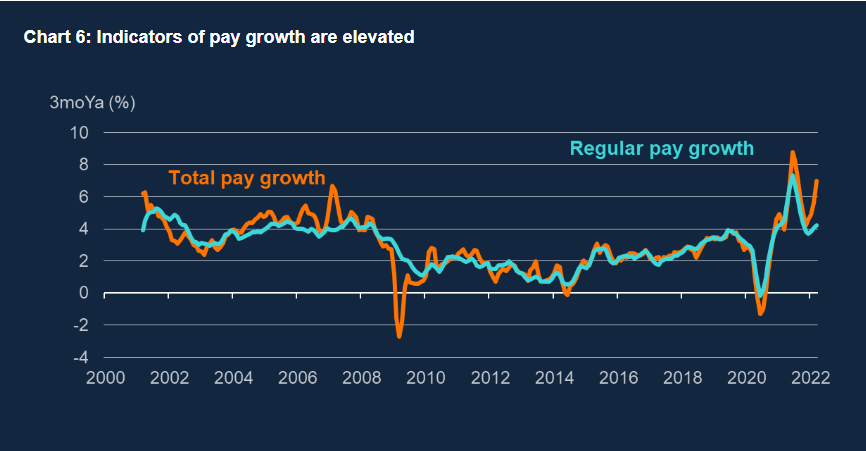

Above: Changes in average rates of pay growth in the UK. Source: May Monetary Policy Report, Bank of England. Click image for closer inspection.

Above: Changes in average rates of pay growth in the UK. Source: May Monetary Policy Report, Bank of England. Click image for closer inspection.

Compare Currency Exchange Rates

Find out how much you could save on your international transfer

Estimated saving compared to high street banks:

£2,500.00

Free • No obligation • Takes 2 minutes

But Monetary Policy Committee members have also said there are various circumstances in which the inflation outlook and conditions within the economy could merit further increases in borrowing costs.

For instance, energy costs could rise further and lead both inflation or inflation expectations to rise again, potentially necessitating action from the BoE.

In addition, wage and salary demands of workers could also follow suit and would likely be perceived by the BoE as something that could stoke more inflation further down the line.

“As members of the MPC have emphasised many times in the past, the outlook for monetary policy therefore cannot be read simply from the MPC’s published forecast. Rather it is conditional on how events evolve,” the BoE’s chief economist Huw Pill said in a May 20 speech.

“If we were to see commodity prices rise further, would this lead to stronger second round effects in domestic wage and price setting behaviour? Or would the real income squeeze implied by higher energy prices lead some of those that left the labour force during the pandemic to seek jobs, easing cost pressures stemming from the tightness in the labour market?," he asked at the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) Cymru Wales.