Surge in UK Unemployment Underway as DWP Reports 950K New Benefit Claimants in Just Two Weeks

- Written by: James Skinner

Image © Adobe Images

Image © Adobe Images

- GBP/EUR spot at the time of writing: 1.1376

- Bank transfer rates (indicative): 1.1040-1.1120

- FX specialist rates (indicative): 1.1200-1.1230 >> More information

The labour market is crumbling as coronavirus containment efforts drive a sharp spike in job losses that could have lifted the unemployment rate as much as three percentage points over the last fortnight, to its highest since June 2014.

Some 950k new claimants have applied for welfare payments in the fortnight between March 16 and March 31, according to the Department for Work and Pensions. This more than doubles the 477k that were said by Department for Work and Pensions Secretary Theresa Coffey to have registered new claims in the nine days to Wednesday 25.

The surge in new claims wipes out 77% of the 1.23 million new jobs created between the referendum of June 2016 and January 2020 while implying a severe increase in unemployment that's likely to lift the jobless rate by 2.7 percentage points to 6.6% for the three months to the end of March.

There were 31.75mn people in full and part-time work during the three months to the end of June 2016 but 32.98mn were employed in the three months to the end of January 2020.

"An increase in the unemployment rate of this magnitude is reasonable given the surge in Canadian and US jobless claims," says Joseph Capurso, a strategist at Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

Official figures from the Office for National Statistics will not confirm the increase until May 19 as they are published with a 45-day lag of the period-end in question, although with preliminary claims data being released ahead of time economy-watchers now have all of the important moving parts required for them to track unemployment rate changes as often as the data are made available.

Above: Changes in full and part-time employment for men and women in the UK ahead of the coronavirus shutdowns. Source: Office for National Statistics.

There were 1.33mn people out of work but seeking it in January, which is the ONS definition of unemployment, and when combined with the total number of individuals in work this made for an unemployment rate of 3.9%.

That jobless rate was close to its lowest since 1973 but it's gone sharply into reverse since the government took serious stock of the health threat posed by the coronavirus and effectively shuttered the economy to slow the virus' run on the population and, in process, prevent the health service from being overrun.

"Going further by assuming that new claims stay at 440,000 a week in the first two weeks of April, then unemployment could rise by 2,237,000 and the [unemployment] rate would soar to 10.4%," warns Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

The government first asked people to avoid pubs, restaurants and cafes before instructing that those businesses all shut their doors until further notice. It's since required that citizens remain in their homes at all times except for in certain limited circumstances, unless of course they're 'key workers' - a potentially new class of citizen who's labour is fundamentally necessary for the continued servicing and operation of a skeleton crewed society.

"It's too soon to assess the lockdown's efficacy, but overseas data suggest three months will be needed. The public supports the lockdown now, but fatigue and concern about the financial costs will grow," says Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Above: Daily changes in the number of new coronavirus infections and related deaths in the UK. Source: UK Government.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced unprecedented measures to support companies and households through the shutdown that's billed by politicians and others as a China, if not prison-style 'lockdown'. Those measures include offers to pay up to 80% of wages to avoid seeing workers lose jobs, tax deferrals and cash grants for companies as well as uber cheap and government guaranteed loans for businesses deemed by state authorities to be 'viable'.

"A further leap in new claims for Universal Credit suggests that the government support designed to keep people employed isn’t working," Dales says. "Our forecast that the unemployment rate will peak at 6% now looks too hopeful."

Those measures could see the government splurging more than £100bn this year alon and such expenditure could easily lift the government deficit by high single digit perentages of GDP this year and next. Some economists see the 2020 deficit potentially coming in above 10% of GDP, which could have profound implications for a Pound Sterling that carries on its shoulders the developed world's largest current account deficit and requires continuous capital inflows from abroad to sustain its value.

"The current account deficit declined to £5.6B in Q4, from £19.9B in Q3. As a share of GDP, it fell to 1.0%, from 3.6%," notes Pantheon's Tombs.

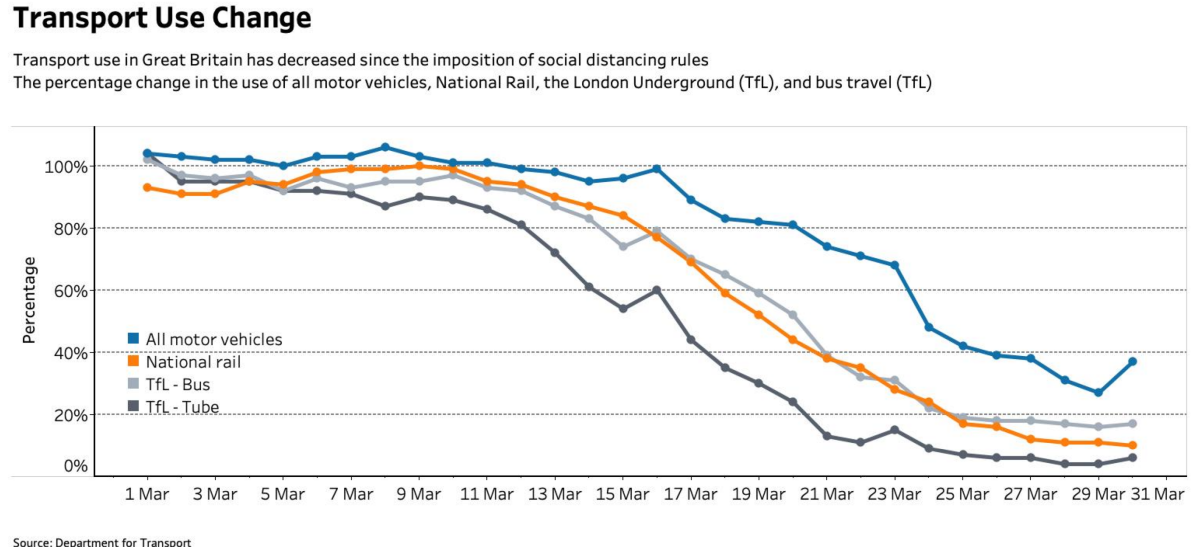

Above: Changes in usage of various forms of transport in the UK.

Should those investors deem the government's efforts to preserve what it can of the economy to be a fiscal expense too far, or more likely one that is perceived to pose such a risk that it necessitates an increased 'risk premium' for holders of British sovereign debt, then Pound Sterling would likely have to pay the tab. And the only way any currency could pay such a bill is through a depreciation that, with cash flows measured in foreign currency terms, lifts to a sufficient level the percentage value of the interest coupon paid by government bonds.

In other words, a buyers' strike on the British Pound that lasts until it becomes cheap enough to sufficiently augment the returns of would-be debt investors could be in the pipeline. That's the only way those interest returns can be augmented in a world where the Bank of England (BoE) is crushing bonds yields to death through a £645 bn quantitative easing programme that's already seen it buy up more than 30% of all sovereign debt issued by the government.

This is a substantial driver of some bearish year-end and 2021 analyst views on why the Pound might be found trading near to recent post-1985 lows long after the coronavirus crisis subsides.

"A record-breaking public sector deficit may require additional external borrowing," warns Stephen Gallo of BMO Capital Markets. "The UK's floating exchange rate is an important buffer for the economy in these extraordinary times, and we have penciled in a move to 1.15 at the 9M part of the curve."