UK Economic Outlook is "Promising" says Berenberg Bank

- Written by: Gary Howes

Image © Adobe Stock

Berenberg Bank says an era of higher interest rates should be embraced as it introduces the very real prospect of 'real' growth in the UK economy.

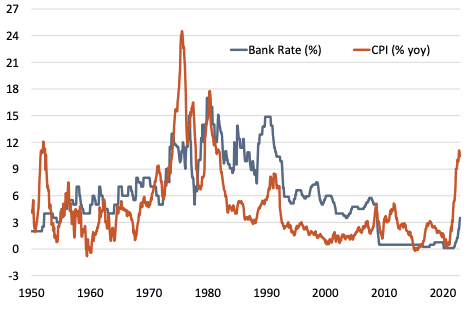

Berenberg - the world's oldest merchant bank - says the era of ultra-low interest rates is now truly over as the Bank of England will almost certainly hesitate to slash interest rates aggressively in future growth slowdowns.

Higher interest rates strike fear into homeowners concerned about the affordability of their mortgages, but economic history suggests higher rates force companies to "shape up" says Berenberg.

Economists at the bank anticipate UK companies will invest more in their employees now rates are rising, leading to a boost in real GDP.

The era of ultra-low interest rates followed the Great Financial Crisis as central banks responded to conditions of 'no-flation': a time of sub-2.0% inflation in the developed world.

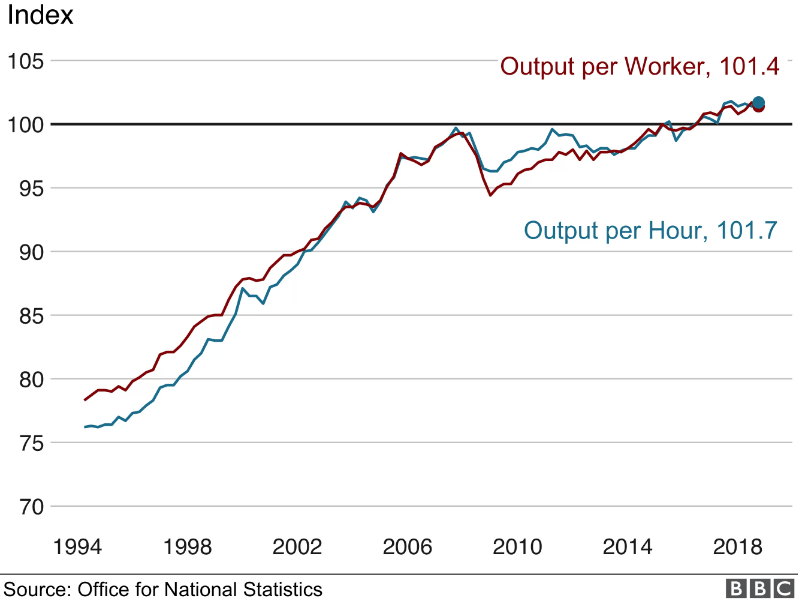

This period also coincided with stagnation in UK economic productivity, something the Bank of England itself has acknowledged is linked to its monetary policy decisions post-GFC.

The productivity loss has often been described as "the lost decade" as worker output per hour fell and ultimately stagnated.

The stagnation came as companies failed to invest in machinery and skills, two key components that make a worker more productive.

Productivity matters: the more productive an economy the more productive its workers which ultimately boosts their earnings potential.

In short, the UK's productivity stagnation is a stagnation in worker value.

But as 2023 dawns, Bereberg is looking for a break from the business-as-usual of the past decade.

"Deflation fears after the GFC allowed the BoE to ease aggressively whenever growth slowed or when the economy fell into recession. But the renewed danger of inflation means that policymakers will need to consider whether easing monetary policy in response to signs of weakness in output growth is worth the risk," says Kallum Pickering, Senior Economist at Berenberg.

Berenberg's research finds that previous periods of high inflation entailed more frequent policy adjustments at the Bank of England, which in turn made for a more volatile interest environment for businesses.

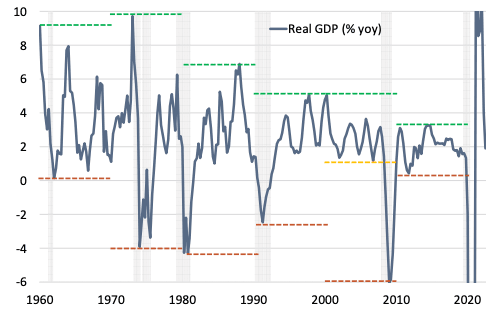

"However, these periods were also associated with stronger average real GDP gains – even during the extreme uncertainty of the Cold War years," notes Pickering.

Above: Declining business cycle amplitude for 50 years. Annual percentage change in real GDP. Shaded areas show recessions. Green dotted lines highlight decade growth peaks. Red/orange dotted lines show decade growth troughs. Quarterly data. Source: ONS. Image courtesy of Berenberg Bank.

"Can we therefore be optimistic about the future despite the challenges ahead? Yes," he says. "In one important respect, the outlook is promising."

The analyst says inflation and higher rates now mean more pressure on supply and margins, especially from wage costs, putting companies under greater pressure to shape up.

"By and large, the UK private sector has the means to support long-term investment. Cash balances are high, debt is under control and banks are well capitalised. Over time, expect firms to turn to available technologies - such as big data analysis, 3D-printing and advanced robotics - to raise productivity and decrease waste," says Pickering.

Above: The end of the great moderation in rates and inflation. Bank of England (BoE) bank rate compared to annual inflation as measured by the consumer price index. Monthly data. Source: ONS, BoE. Image courtesy of Berenberg Bank.