Euro Weakness: What do Bond Yields Tell us About the Potential for Recovery?

Above: Kit Juckes of Société Générale

The Euro has weakened due to long-term negative growth prospects but could a restocking drive keep the single currency supported?

The European Central Bank's late-October decision to reduce stimulus is widely seen as a vote of confidence in the health of the Eurozone economy but markets opted to sell the Euro with bulls apparently wanting the ECB to go further and faster on reducing stimulus.

And looking ahead, we are told the Euro will not deliver fresh highs against the Pound or US Dollar until the longer-term prospects for growth pick up. Investors do not see growth, inflation or interest rates in the Eurozone going up substantially in the long-term says Société Générale's Head of G10 FX Strategy Kit Juckes.

Growth leads to spending and higher inflation which makes central banks put up interest rates, higher interest rates in turn tend to strengthen a currency as foreign investors tend to move their money to where it can earn more interest.

For the rally to begin again the longer-term view of growth in the Eurozone would need to improve, says Juckes.

Eyes on Bond Yields

How do we know what investors think about growth and inflation in the long-term? How can we possibly tell?

The answer is through the prism of complex financial alchemy using the bond markets as a telescope into the 'future'.

Bond's (Bunds in German) are long-term loans whose price is sensitive to inflation.

This is because if inflation rises, the value of the loan interest repayments (and the final repayment of the original loan amount) fall due to erosion by inflation.

The price of the loan, therefore, reflects investor's long-term views on inflation, with corrosive higher inflation leading to a fall in bond prices.

Whilst bond prices fluctuate, the original bond loan amount always remains the same and must be repaid to the bond holder in full at the end of the term.

If the bond price falls due to higher inflation expectations, then the buyer who buys it at the lower price will get relatively more principle at the end of the term - for what he paid - than someone who paid a higher price when inflation expectations were lower.

This increase in the bond holder's profit is reflected as a percentage in the form of the bond's 'yield'.

The yield is therefore correlated with inflation expectations.

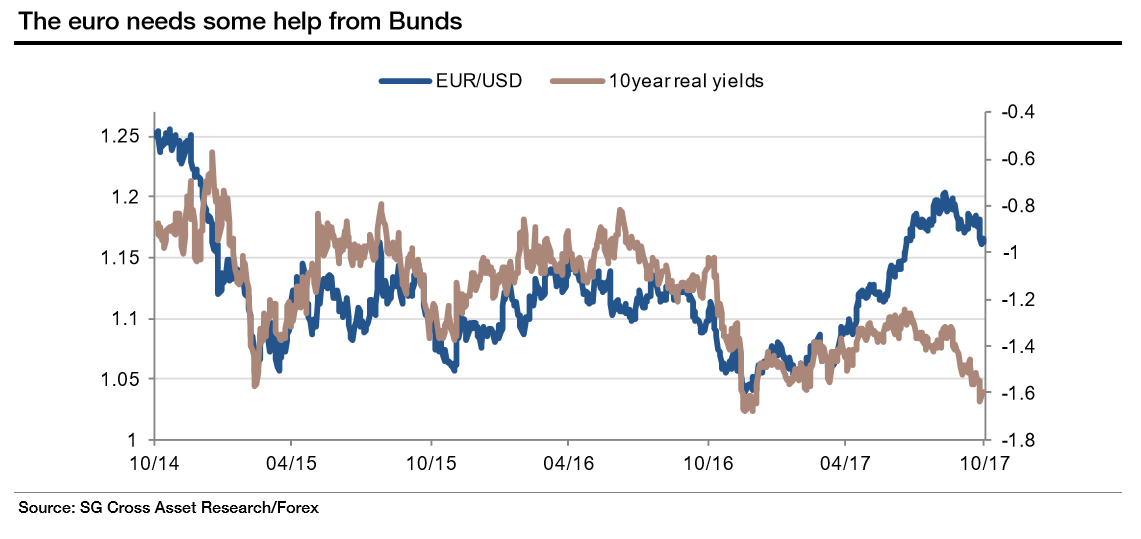

According to SocGen's Kit Juckes, the EUR/USD exchange rate is more correlated to 10-year bond yields than shorter terms - which explains his emphasis on longer-term expectations.

The Euro's correlation with short-term, 2-year bonds has almost completely broken down (more specifically the 2-year US/Euro bond yield differential shown below which is analagous):

At least with the 10-year, the yield and EUR/USD peaked at the same time (see below).

A recent study by SEB's FX Strategist, Richard Falkenhall notes how 10-year US Treasury Bond yields provided the best correlation for EUR/USD suggesting US bond yields are now the primary driver for the pair.

This makes sense given the argument here that Bunds are currently unengaged.

Recently the European Central Bank announced it would be reducing its stimulus programme because improvements in the Eurozone economy meant the region does not need stimulus anymore, however, the ECB was cautious about ending stimulus and this suggested it was not very confident about growth going forward.

The ECB stimulus programme involves the buying of bonds from financial institutions (FI) at a rate of 60bn per month in order to provide those FIs with excess liquidity which can then be more cheaply lent out into the real economy, to drive growth.

The ECB's decision to reduce - or taper as it is known - stimulus to 30bn for 12 months, means it will be buying fewer bonds - including 10-year ones, and this will artificially reduce demand for them theoretically leading to lower bond prices, which in turn will increase their yield.

Yet Juckes makes the point that this is not what in fact happened - yields did not go up when the ECB announced its stimulus tapering or reduction strategy, not sustainably.

"Bund yields have fallen back, from 60bp to today's 36bp. A slow-motion tapering doesn't drive term premia back up. Investors aren't being crowded back into Bunds and won't be until the authorities are net sellers of bonds again," he said.

This suggests a stronger gesture of confidence is required from the ECB to push both yields and the Euro higher.

This might be the case if the ECB completely axed stimulus, or started to sell the huge pile of assets it has already accumulated after years of bond-buying stimulus.

"Bund yields may be a necessary condition for the EUR/USD correction to come to an end. And in the long run, it will be when (if) the ECB starts running down its balance sheet that will be the driver of the Euro becoming over- rather than under-valued. That date remains somewhere out there in the dim and very distant future," says Juckes.

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider by getting closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank for international payments. Learn more here.

Euro Restocking Drive

Morgan Stanley acknowledges the inertia in yields but does not see it as predominantly reflecting a negative outlook for Eurozone growth as Juckes does.

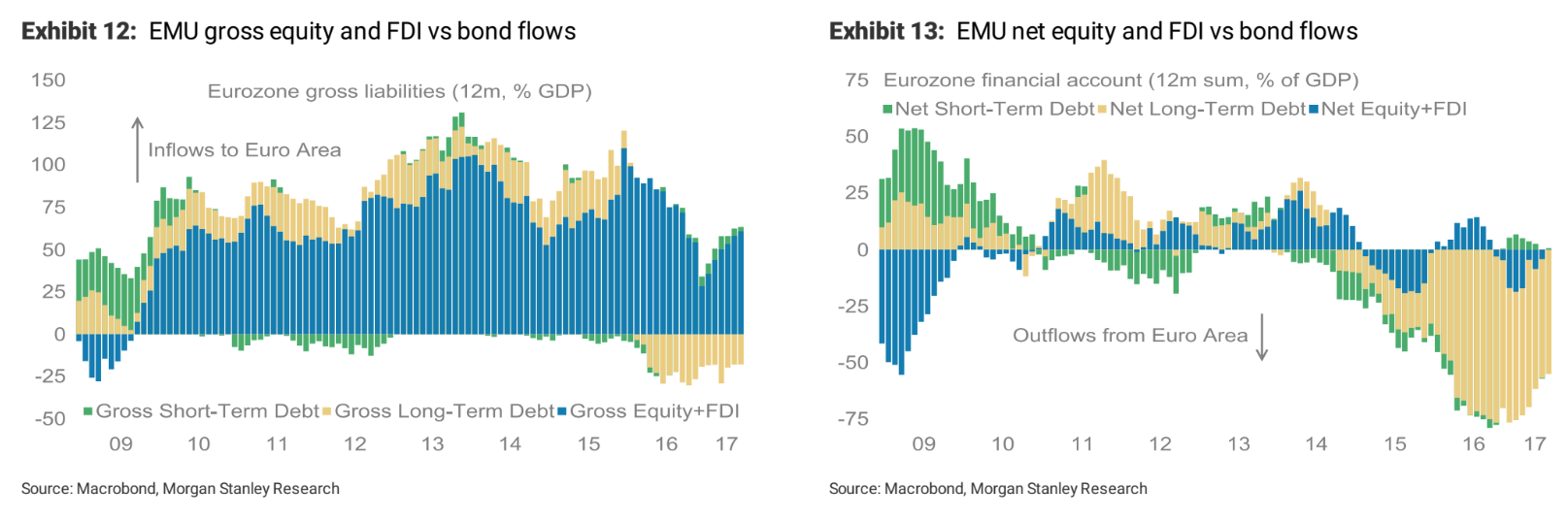

Strategist Hans Redeker argues that debt is still in demand, keeping bond prices high and yields low, because the Euro is underowned internationally, and the increased demand for debt comes from reserve managers and investors restocking their reserves by borrowing increasing amounts of Euros.

Another explanation is that the outbound debt is being used to fund carry trades which is an investment strategy in which investors borrow money in a low-interest currency, such as the Euro or Yen, and park it in a higher interest currency, pocketing the difference at no personal risk.

If this is the case, it would suggest investors saw interest rates remaining low in the Eurozone longer-term.

Yet Morgan Stanley argues that this interpretation of the data cannot be squared with the the net surplus flow of foreign investor cash into European equities.

This paradoxical state of affairs in relation to the flow of money via the region's financial account seems to suggest investors are overall quite optimistic about growth in the Eurozone or they would not be buying a net surplus of European stocks and shares.

'Exhibit 12' shows the difference between the balance of Eurozone financial liabilities - with the blue positive net for stocks and shares and the beige negative deficit for long-term debt.

'Exhibit 13' below shows the large outflow of "Net Long-Term Debt" from the Eurozone which is money the Eurozone is lending to the rest of the world.

Taken together with Juckes's analysis it may explain why lending remains so cheap and is a possible reason for why 10-year yields remain stubbornly low.

In explaining the large net outflow of long-term debt the carry trade interpretation is a worse fit.

"This interpretation does not consider how under-owned the EUR is by global investors and even more importantly, does not take into account the change in the structure of gross and net flows," says Morgan Stanley's Redeker.

"Globally, real money accounts run low EUR net exposures. Pension funds and other institutional investors have currency hedged their EUR denominated assets, while FX reserve managers have reduced their EUR holdings since the Global Financial Crisis from 28% to 20% of total holdings. EMU net bond flows have stayed relatively constant

Redeker concludes that the outlook is positive for the Euro "should EMU’s economic performance stay strong, equity and FDI related inflows should stay EUR-supportive."

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider by getting closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank for international payments. Learn more here.