Sterling's Flash-Crash Solved and Extreme Market Dysfunction is to Blame

The reason for the infamous Pound Sterling flash-crash of October 2016 has finally been diagnosed by The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) who have released a report into their investigation on the matter.

The British Pound suffered an extraordinary free-fall in early Asian trade on Wednesday October 5 2016 with the GBP/USD exchange rate plummeting to a low of 1.06 - or 1.12 - depending on who provides your data.

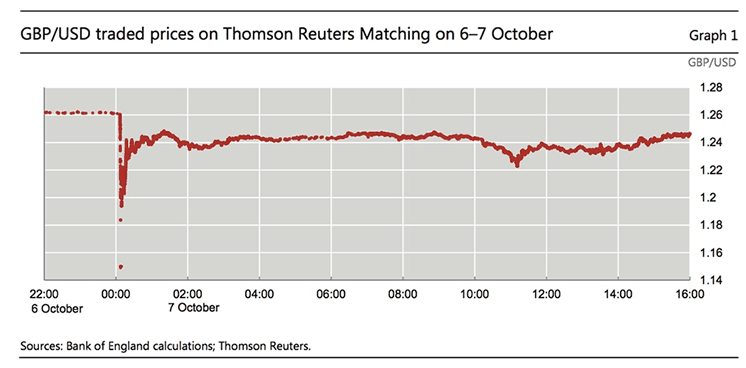

The BIS cite the following chart though:

Shortly after midnight British Summer Time (BST), equivalent to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) plus one hour, on 7 October, trading volumes picked up sharply and Sterling began to depreciate against other currencies.

Over a period of around eight seconds (00:07:03 to 00:07:11 BST), Sterling fell from 1.2600 to 1.2494 against the Dollar, based on the Reuters mid-price.

During this time, around £252 million of GBP/USD was traded on Reuters, of which the vast majority represented so-called ‘aggressive’ sales of Sterling – pointing to a very significant imbalance in order flow.

Despite the magnitude of the move and the volumes transacted, GBP/USD bid-offer spreads remained little changed until around 00:07:14 BST and measures of the price impact of transactions over this period were relatively low.

And it was not just the Pound-Dollar exchange rate that was impacted - all GBP-based currency pairs sold-off in sympathy.

€52 million of EUR/GBP was traded according to Reuters.

Finding the cause of the crash is important in order to avoid such market-shaking events in the future.

Indeed, even today the impact of the crash are being felt with institutional forecasters reliant on where various Pound-based currencies actually fell.

The problem is, different data providers gave different lows which in turn gives technical analysts different forecast targets.

What Caused the Crash?

The report from the BIS shows that a number of factors came together and drove the move as opposed to one single trigger.

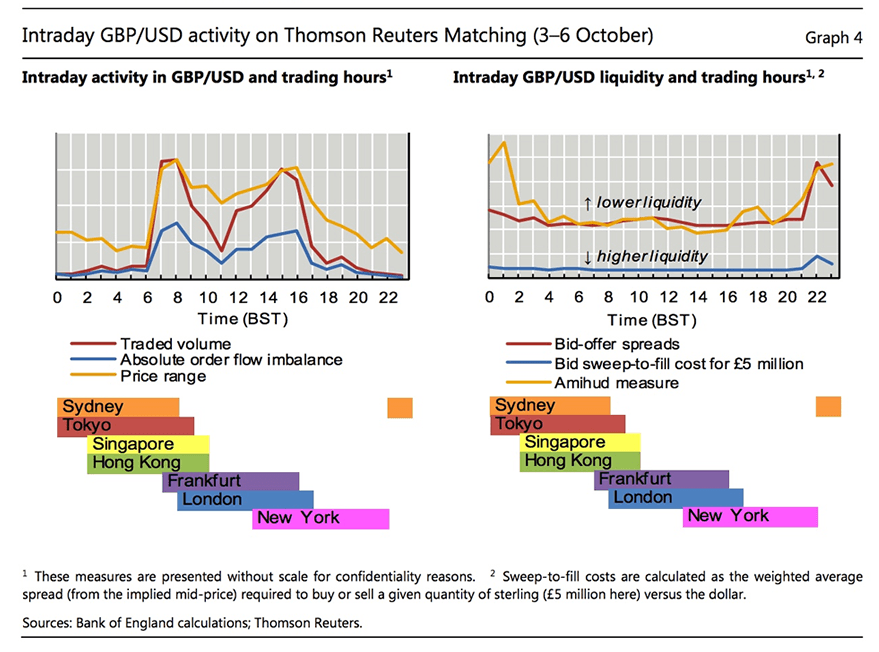

The report finds that the time of day played a significant role in increasing the Sterling foreign exchange market’s vulnerability to imbalances in order flow.

Three Phases

The event can be split into three distinct phases say the BIS:

First, the early phase of the move, during which sterling depreciated rapidly from 1.26 to around 1.24 against the dollar in response to significant selling flow, but in an orderly fashion and with broad participation on key venues.

Second, a period of a number of minutes of extreme dysfunction during which Sterling fell further, rebounded and then traded in a wide range. This phase involved lower volumes and narrower participation, pointing to a greater role for the actions of individual market participants as a driver of the sharp moves.

Third, the gradual recovery in market liquidity over the hours that followed.

Market Dysfunction

Of interest to us is the BIS finding that a dysfunctional market played a role in the flash-crash.

And, to complicate matters a number of factors contributed to and amplified this market dysfunction.

The BIS cites:

Significant demand to sell Sterling to hedge options positions as the currency depreciated.

The execution of stop-loss orders and the closing-out of positions as the currency traded through key levels may also have had an impact.

A media report released shortly after the move began, which would have been interpreted as somewhat sterling-negative, is only likely to have added marginal weight to the move as it did not contain new information.

“These factors appear to have contributed to the mechanical cessation of trading on the futures exchange and the exhaustion of the limited liquidity on the primary spot FX trading platform, which encouraged further withdrawal of liquidity by providers reliant on data from those venues,” say the BIS.

Time Zone

The BIS finds that the market also failed because the crash occurred during Asian trade and was outside of London’s reach - or Sterling’s ‘core timezone’ - and therefore bank staff who were less experienced in trading Sterling were at the helm of the market.

Apparently, these traders had lower risk limits and risk appetite, and with less expertise in the suitability of particular algorithms for the prevailing market conditions.

But What About the Fat Finger?

A favourite default explanation for any sharp move in markets is the fat finger explanation - essentially some idiot has made a mistake.

While the BIS find no evidence of a fat finger error, they do not rule it out.

They also do not rule out market abuse.

“But there are little, if any, hard data to substantiate them,” say the BIS.

Markets are Different Today

What we have heard from a number of old-school traders since the flash-crash is that this would never have happened in the time before algorithms ruled the markets.

Before algorithms there were actual people on the other side of the trade, thus mistakes were less liable to happen.

The BIS believe that this event does not represent a new phenomenon but rather a new data point in what appears to be a series of flash events occurring in a broader range of fast, electronic markets than was previously the case in the post-crisis era, including those markets whose size and liquidity used to provide some protection against such events.

"I know all of us old interbank market dinosaurs will be driving you crazy with our “I told you so’s”, but we did!" said Sean Lee of Forextell at the time. "Whether for regulatory, commercial or technical reasons, the very core of the FX market no longer exists; namely the hundreds of interbank traders who sat at their desks and provided pricing no matter what the conditions."

No Major Losses Incurred

There are a number of commonalities with previous flash events and similar episodes.

Unusually, there were few spillovers to other currencies or asset classes.

“And no systemic financial institutions incurred material financial losses in this instance. This might point to market participants having learnt lessons from past episodes,” say the BIS.

Furthermore, “flash events to date have generally proved short-lived and without immediate consequences for financial stability. And the same appears to have been true of the sterling event.”

The BIS recommends that policymakers to continue to develop a deeper understanding of modern market structure and its associated vulnerabilities.