Euro-to-Dollar Rate Forecasters Doubt Upside Potential amid Renewed Break-up Fears

- Written by: James Skinner

© Pound Sterling Live

- EUR/USD spot at time of writing: 1.0936

- Bank transfer rates (indicative): 1.0433-1.0508

- FX specialist rates (indicative): 1.0773-1.0839 >> More information

The Euro-to-Dollar rate outlook has dimmed now the debate over debt mutualisation has opened the door to a renewal of concerns about a possible Eurozone break-up, leading some influential forecasters to doubt the upside that's still baked into market expectations for the single currency this year.

Markets entered 2020 expecting the Euro to hit 1.15 by year-end, implying a low single-digit increase from last year's levels and although this consensus or average of all selected projections has since dipped to 1.14, some forecasters are increasingly doubting the upside potential of the single currency in the short-term.

This is after the European institutions, all barring the European Central Bank (ECB), arrived late on the coronavirus scene only to become bogged down in a quarrelsome debate about debt mutualisation that has reopened old wounds for some on the continent, inciting concerns about a possible longer-term break-up of the bloc that could weigh on the Euro in the weeks if-not months to come.

"The FX market does not value the EUR based on a single outcome. Its value is a cocktail of various possible paths, with shifting probabilities. One such possible path is a fragmentation of the Eurozone due to the potential economic and political repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The market does not appear especially preoccupied with this topic, and is perhaps more fixated on the near-term cyclical outlook than grander considerations about the structural integrity of the Eurozone project. This indifference might be challenged in the coming months," says David Bloom, head of FX research at HSBC.

The Eurogroup finance ministers agreed last Thursday a €540 billion aid package to help countries cover the cost of containing the coronavirus that's turned Europe into a Western Wuhan since late February, which is set to be rejected by some national leaders. This makes the the April 23 video conference meeting of the European Council thr next flash point that Bloom sees posing "downside risks" the single currency.

Above: Euro-to-Dollar rate shown at daily intervals.

Last week's deal includes €240bn of European Stability Mechanism (ESM) funding for those members who choose it, with the only condition being that the money is spent on the coronavirus health response or other things related to it. The package also provides capital to the European Investment Bank so that it can offer up to €200bn of loan guarantees and makes provision for a €100bn European Commission unemployment insurance scheme.

"In our view, these actions significantly reduce certain tail risks related to bond market access, and therefore should lower the probability of a sharp Euro depreciation on EMU break-up fears. However, we still do not see a compelling argument for Euro appreciation over the near-term," says Zach Pandl, global co-head of foreign exchange at Goldman Sachs, of the Eurogroup package. "We expect more of the same in the weeks ahead: higher EUR on risk rallies and weaker EUR on risk drawdowns, and limited idiosyncratic moves."

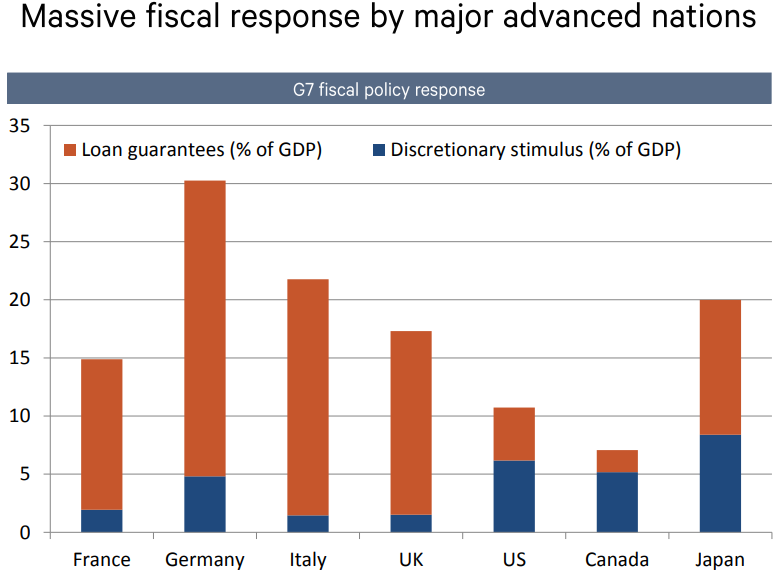

The Eurogroup aid package is worth 4.5% of Euro area GDP and comes in addition to the extensive array of other measures already announced by national governments, although the process of agreeing the deal and fact that it doesn't endorse the corona bonds proposed by nine countries in March has left a sour taste in the mouths of some Eurozone governments.

"The day after it was agreed Portugal’s Prime Minister stated “We need to know whether we can go on with 27 in the European Union, 19 (in the Eurozone), or if there is anyone who wants to be left out. Naturally I am referring to the Netherlands,” notes Michael Every, a strategist at Rabobank.

Above: Major economy fiscal policy responses as a portion of GDP. Source: Berenberg.

Italian Prime Minister Guiseppe Conte said at the weekend he intends to reject the Eurogroup plan in the April 23 European Council meeting, where it must gain unanimous approval to enter into force, over opposition to mutualised debt in Europe. Conte is also said to oppose the ESM aspect of the plan because it's a crisis era bailout fund through which national finances were hijacked by a 'troika' of international lenders including the European Commission, ECB and International Monetary Fund.

"For better or worse, the way in which countries help or do not help each other in the acute phase of the pandemic can shape perceptions of European integration for a long time to come," warns Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg. "With every week in which the current dispute makes headlines in Europe, the risk of an anti-euro backlash in public opinion is rising. According to Tecne poll from 9-10 April, the share of Italians that would vote for “leave” in a EU membership referendum was up by 20ppt to 49% relative to a previous poll from late November 2019."

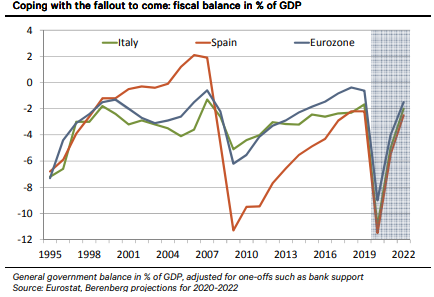

The troika experience brought years of austerity that eventually imposed heavy political costs on those involved with it domestically but not without first making Italy a Eurozone laggard in the years since the crisis while leaving it with a still-bloated balance sheet that now constrains its ability to contain and clean-up after the coronavirus. Hence the call for 'solidarity' in the form of corona bonds.

Conte until recently the worst coronavirus outbreak in Europe, where five of the world's six largest hotspots are, and Italy still had the highest death toll on Tuesday. Italy was the first European country to go into 'lockdown' to slow the spread of the virus, which is now believed to have reached its 'peak' in Italy.

Above: Expected budget balances for Italy, Spain and Eurozone as a portion of GDP. Source: Berenberg.

"We see larger contractions in Italy and Spain than northern Europe," says Sven Jari Stehn, an economist at Goldman Sachs. "We also see a striking north-south divide in the degree of the labour market deterioration. We expect the unemployment rate to rise to 23% in Spain and 17% in Italy, but only see a limited increase in Germany (to slightly above 5%) and France (about 10%)."

Southern Europe's economies were weakest to begin with but have been hit hardest by the coronavirus and might already be struggling to raise money from the bond market if it wasn't for the ECB expanding its quantitative easing programme by €850bn and tilting its purchases heavily toward Italy and Spain.

ECB buying may have prevented those countries from effectively being shut out of the market by prohibitively high interest costs but the bank will eventually have to underweight both in order to abide by its 'capital key.' This would then risk encouraging a spike in yields to the prohibitive levels seen in 2012.

"Employment sensitivity is higher in the south, both because activity is more concentrated in labour-intensive sectors and because short-time work schemes are less generous. The north-south divide in terms of labour market outcomes highlights the importance of a risk-sharing mechanism that allows southern European economies to provide sufficient fiscal support to their economies during the coronacrisis," says Kavya Saxena, a Goldman colleague of Stehn's.

The Eurogroup's €100bn unemployment insurance scheme is the same kind of "short-time work scheme" referred to by Goldman and although it might limit the downside for labour markets, it's not placated Italian leaders who still demand corona bonds; debt jointly issued by all Eurozone countries.

Above: Euro-to-Dollar rate shown at monthly intervals.

Concerns about bond market access and a possible austerity quid pro quo from other countries via the European Commission are what prompted calls for mutualised debt to sit alongside the mutualised Euro currency but the idea has been rejected by Central and North European members who fear the domestic political implications of footing the bill for a 'periphery' often painted and perceived as profligate.

Finance ministers left national leaders a European Council escape hatch in the form of a pledge to discuss a "recovery fund" and "innovative new financial instruments," on April 23 or after but if they don't jump through it then resentment could build in the 'periphery. That and any resulting concerns about a possible break-up of the currency union further down the line would hardly be conducive to the rising Euro envisaged by the consensus this year.

Eurogroup President Mário Centeno was reported by Reuters on Wednesday to have told Italy’s Corriere della Sera last week that corona bonds have not been ruled out before going on to talk about the recovery fund that will be discussed at next week's meeting.

"This creates downside risks for the EUR from a structural perspective with any increase in the probability attached to break-up, however small that probability might remain, likely to pressure the EUR," says HSBC's Bloom. "History shows that the Eurozone finds the political will to respond to any existential threat to the EUR, and we would expect a similar resolve were the COVID-19 pandemic to create a new challenge to the EUR project. It just might get worse for the EUR before that pan-European political resolve becomes more apparent."