The Rise of Robots: A Threat or An Opportunity?

Advances in artificial intelligence mean a new age of mechanization could be dawning, bringing challenges and opportunities to workers, businesses, and society at large.

Walk into your nearest supermarket and you will see that where once stood lines of checkouts manned by people there are now mostly self-service checkouts manned by shoppers themselves; its a quotidian example of how machines have come to replace workers.

Whilst this is nothing new - as far back as the 19th century the 'Luddites' took to damaging factory machines as they saw them replacing their artisanal skills - the speed and scope of the encroachment is set to increase exponentially over coming years.

A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) into automation in the workplace says that as much as 30% of UK jobs could be under threat due to breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), and in some sectors almost half of the jobs could be at risk.

The report notes that an estimated 10 million workers in the UK could be at risk of losing their jobs over the next 15 years as a result of robots taking over their function.

The sectors most at risk are retailing and wholesaling - jobs in shops and warehouses - where 2.25 million jobs are under threat.

Also at threat are jobs in manufacturing where 1.1m jobs could be automated, followed by 1.1m in administrative and support services and 950k in transport and storage, where self-driving cars and lorries could cause a robot revolution in delivery driving.

Fears that robots could steadily take over more and more human roles, leading to higher unemployment, increased inequality and potentially even doomsday scenarios in which disgruntled workers rise up against the 'machines' has pushed automation into the political mainstream.

The Labour party is now advocating a tax on robots to offset the cost of the redundancies they cause, an idea similar to that of Robert Schiller, the Nobel prize-winning economist who said the scale of the transformation in work practices caused by automation would be such over coming years that a "robot tax" should be considered to support those the machines make redundant.

Yet critics of the proposal say fears of a robot takeover are overexaggerated and misinformed, and instead of viewing the new age of automation with paranoia people should be embracing it as a positive development - both for jobs and the economy.

"Historically, concerns about the impact of mechanization have been unfounded. The creative destruction brought about by new technology has boosted productivity, raised living standards and created new job opportunities," says the right-leaning think-tank, the Centre for Policy Studies in a recent report entitled " Why Britain Needs More Robots."

The CPS report cites a study by management consultants Deloitte Touche which says that although automation replaced 800k UK jobs between 2001 and 2015 it also created 3.5m new jobs.

And whilst the next stage of mechanisation may be more far-reaching the report suggests that studies of the number of jobs at threat of automation in future decades may be overexaggerated.

"The figures for “jobs at risk” are likely to be overestimated, as they only consider whether a task can potentially be automated, not whether it is economically sensible for that to happen."

They cite a further study by the OECD which says that whilst more 'tasks' may be automated that does not mean that 'whole professions' or roles will be replaced.

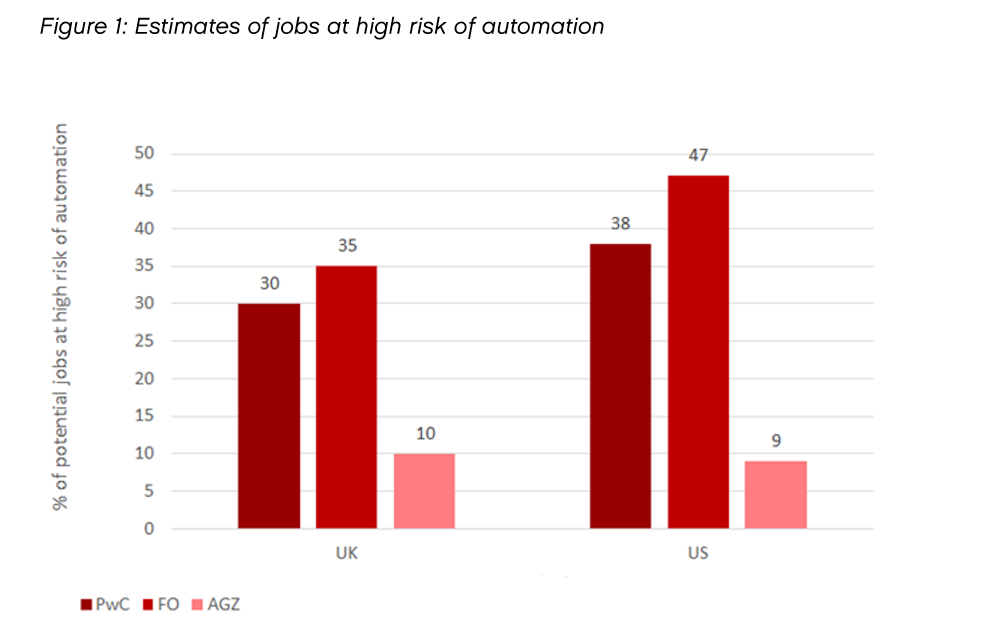

The OECD study (AGZ) places the number of jobs at risk from automation at only 9% generally and 10% in the UK, which is a lot lower than the 30-35% posited by the PwC study and another report (FO) from Oxford academics Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne.

One industry the increase in automation will not destroy is the tech sector itself (not yet anyway) which, in fact, stands to expand.

Whilst the number of new jobs in tech cannot fully compensate for those lost through automation, the exact knock-on effect from creating new applications, in terms of the support and maintenance jobs it creates, could mean the net effect is actually neutral.

"Indeed, some estimates suggest that for each job created by the high-tech industry, around five complementary jobs are created," says the CPS report.

The UK in Focus

The United Kingdom may be less prone to automation compared to other countries according to the PricewaterhouseCoopers study.

Germany, for example, could be more at threat from robots as it has a larger manufacturing sector.

The UK has a large financial sector which is more difficult to automate especially as the city of London specialises in international finance which requires even more complex functions.

The polar nature of the robot polemic also ignores significant synergies, according to a report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in which robots and humans work side-by-side in complementary roles, such as robots in warehouses helping humans with the more dangerous heavy lifting tasks and robot room service in hotels freeing up staff from time-consuming room delivery duties.

Much of the commentary on automation hyper-focuses on the "spectre of job losses" says the CPS study, ignoring many of the benefits.

Robots, automation, machines tend to boost productivity, which is defined as the amount of work achieved by a single individual.

Take the example of a combine harvester.

By using a combine harvester one man can do the work of 50, if not more, thus boosting productivity in agriculture significantly, and increased productivity boosts wealth.

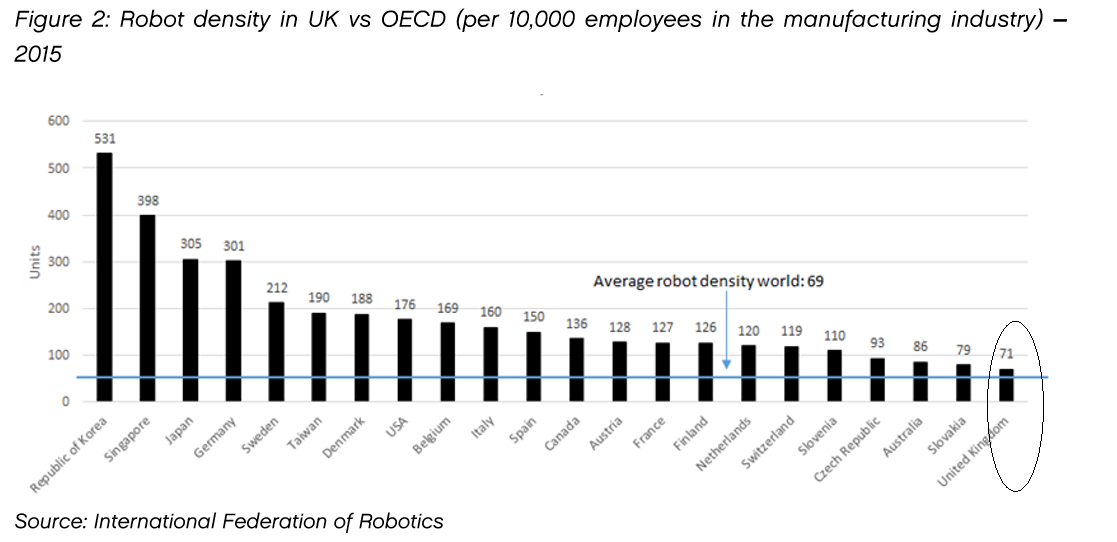

In the UK productivity is lower than in most other developed countries, and the mystery of why this is could be due to the relative lack of automation.

The UK has fewer robots per 10,000 workers, at 71, compared to Germany, which has 301.

For the number of robots, the UK is ranked 22 in the world behind Slovakia.

One reason put forward for the UK's lack of productivity is that automation is low, and this is due to the larger pool of low-paid unskilled labour in the UK.

"The boost in productivity from further mechanisation could help to offset the economy’s other problems, such as high industrial electricity prices (by increasing demand) and major skills shortages in many areas," says the CPS report.

Other benefits from higher productivity through automation could be from lower production costs leading to cheaper products, which could boost demand and thereby economic growth and jobs.

For example, if mechanisation could build cars more cheaply and prices in showrooms fell, more people might buy a new car which could lead to more jobs for salespeople in showrooms, and possibly better-paid work due to higher aggregate sales and turnover.

Income Inequality

The argument that automation increases inequality is based on the view that the increased productivity from mechanisation results in greater profits for the business owner but not for workers who are unlikely to see an increase in their wages, or worse still could be made redundant.

Yet the CPS study argues that there is no evidence of income inequality (not wealth that is), which, "has been shrinking over the past few years, rather than rising, with the UK’s Gini coefficient falling from 33.7 in 2010/11 to 31.6 in 2015/16."

The Gini coefficient is a statistical method of measuring inequality by measuring the average dispersion of incomes around a mean.

The nearer to zero the result the more equal the society.

But mechanisation can leave workers more vulnerable as tasks become more operational (ie operator the robot) rather than skill-based (doing the activity yourself).

To this extent worker's roles become easily replaceable and it is more difficult to assess the 'added value' brought by an individual worker to the role - take for example the two examples of a machine operator compared to a skilled assembly line worker.

The machine operator can be more easily replaced than the skilled assembly line worker and has less leverage to negotiate better pay and conditions.

The solution, however, may not be in trying to resist the march of technology which has its own irresistible logic, but rather, to provide more protection to workers via a higher minimum wage and support services for workers made redundant by machines.

Such support services would help them to adapt to new working conditions, or even change profession and could come in the form of better and wider access to adult education so replaced workers can re-skill for another role.

Whilst we don't know what the next revolution in mechanisation will look like and how far-reaching the effects on society will be, it is likely that the best solution may not be to outright hinder technology and view it as a threat.

Technology, is, for all its ills, wealth creating and the problem is how best to use the greater wealth created for the greater good.

How do we help make vulnerable workers feel more secure without increasing inefficiency, and how can we support redundant workers with access to new educational opportunities so that can re-skill and continue being productive citizens?

These may be the new questions politicians will be facing as the next dawn of mechanization begins.