From Britain to Beirut and Lebanon to London: When Currencies and Nations Fall

- Written by: Dario Garcia Giner, the-blindspot.com

"What shitflation (and shrinkflation) speaks to is the dissolution of our methodologies to calculate price increases. In that regard, it is an insidious phenomenon, reminiscent of the breakdown in price signalling that helped contribute to the fall of the USSR."

Image © the-blindspot.com

This article is a reproduction of a piece titled "When Currencies (and Nations) Fall; The Case of Lebanon’s Bad Data" and published by https://the-blindspot.com/. The original can be accessed here and appreciative readers could find details of subscription offers here.

The dramatic plunge in sterling and UK gilt prices following Kwarteng’s unsupported tax cuts announcement drew many to radical conclusions.

Whether a fatal undermining of Britain’s post-90s fiscal responsibility or displaying a counter-intuitively long-term perspective, the spectre of Black Wednesday’s governmental incompetence is echoing through Westminster’s halls.

Perhaps it’s time for Britons to learn from the difficulties already being experienced by formerly prosperous countries.

Cue Lebanon.

In more or less constant turmoil for the past 80 years, the monetary charade underpinning its edifice collapsed in 2019. A combination of the Lebanese government’s attempt to tax WhatsApp use, ongoing petrol and electricity shortages, as well as the devastation from the shock ammonium nitrate explosion of August 4 2020 sparked what is now popularly referred to as the October 17 “revolution”.

Though most states that failed never got out the door, Lebanon, on the contrary, was once a genuinely high-flying nation. Its recent crash into the morass of a ‘third world’ economy offers a better cautionary tale of the risks facing the West than most others.

In Lebanon, as with Argentina or Cuba, there is a unique and romantic mystique associated with the remnant reminders of its former greater self.

This is not to pretend that Lebanon is totally analogous with Britain – far from it. But should Britons need to turn to anyone for lessons on how to fall from prosperity gracefully (or not), it’s hard to think of a better candidate than the Lebanese.

Lebanon’s ills may not predict what could happen to Britain, or other Western economies catching the de-globalisation illness du jour, but they may foreshadow some events.

Chief among them is the difficulty of making informed decisions if price-signalling mechanisms relied on by central bankers and policy-makers stop working.

On a recent visit to Beirut, I asked one informed local whether Lebanon was merely a country that had caught the de-globalisation flu pre-emptively. He reflected: “it is really surprising to me that you should say that, as I have been thinking this for a very long time…”

..

Data Challenges in Collapsing Economies

Britons are currently wondering about the competence of those in charge. Questions have been raised about the Bank of England’s delayed response to rising inflation. Likewise, though voters already baulked at the cost of Covid-19 furlough programmes – Liz Truss’ energy lifeline is set to cost almost twice as much. This, many claim, will imperil governmental finances in what is already a dangerously inflationary environment.

It’s easy to blame seemingly idiotic leaders. But that is not necessarily fair. Their incompetence may not be down to them. It could be the function of a wider systemic forces, which have compromised signals and data, impeding sensible decision-making more broadly.

Observing Lebanon, it seems the first casualty of the crisis is definitely data.

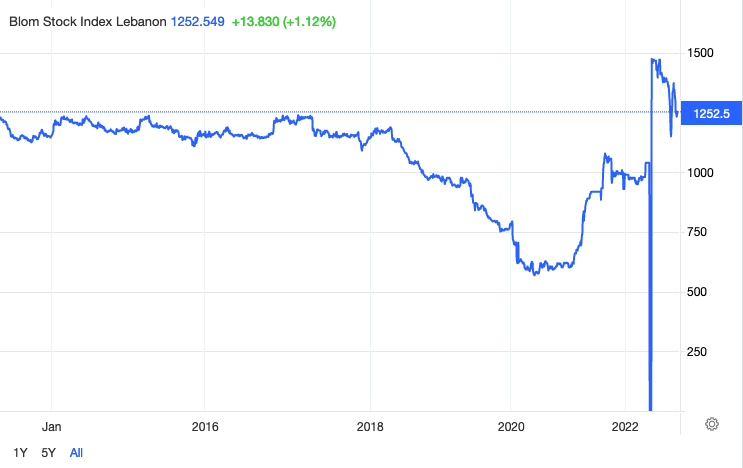

For instance, despite the apparent economic malaise, the local Beirut Stock Exchange’s main Index, BLOM does not seem to be doing terribly;

But hold up….

It’s not that graphs such as the above are misleading – it’s that they are useless. Zimbabwe’s stock market notched up equally impressive gains at the peak of its troubles in 2008.

Like Zimbabwe at the time, Lebanon has been undergoing a shattering devaluation of its local currency, the Lebanese pound, since at least August 2019. The Central Bank, burdened by calamitous sums of debt, has as a consequence put capital controls and haircuts in place since October 2019 and fixed the value of the Lebanese Lira at £L8,000 to the dollar. This has in turn given rise to three distinct exchange rates in the country.

- Lebanese pounds (£L)

- Lebanese/local dollars or ‘lollars’ (US dollars exchanged at the official £L8,000 central bank rate and in late August 2022 worth approximately 30 per cent of a real dollar).

- “Fresh dollars” (exchanged at the black market rate, which currently sits around £L33,000 to the dollar).

The above has made a mockery of the rates institutions are legally obliged to display, impairing the capacity to formulate solid, official economic data and GDP.

..

Damned lies and statistics

Lebanese unemployment figures are similarly difficult to assess. As Marc Koussa, a macro strategist at Credit Suisse, told the Blind Spot, these have been officially running at 29.6 per cent since January 2022, but are far from precise. “In good times, true unemployment was between 20-30 per cent.”

Compounding the problems are the twin powers of shrinkflation and “shitflation” – the art of reducing either the weight or the quality of a product instead of increasing prices.

Lebanese shitflation is now very pronounced.

During my visit I was heartily advised by friends to beware the food (even at luxury restaurants) for three reasons:

- Power cuts mean that if the power generators don’t kick in immediately (and they don’t always), food can quickly rot: avoid raw fish.

- Water supply and irrigation issues mean many vegetables and fruits are watered with toxic water: avoid those which are uncooked, and remove the skin from vegetables and fruits whenever possible.

- Lowering food maintenance standards means a food-borne virus is going around: good luck.

And then there’s the fact that 12 rounds of the popular Beirut concoction basil and gin at a local bar seemed to have a suspiciously minimal effect on my general lightweight demeanour. (Unlike in London, where just a sniff of a pint recently had me out for the count).

But shrinkflation is also having an effect in different ways. For instance, Lebanese fans of the imported Iberian luxury beyota ham are observing a marked decrease in the products’ weight and size among those retailers still stocking it.

Others have dropped the ham entirely or substituted it with cheaper alternatives.

A similar story applies to the pharmaceutical sector, says Dr. Salam Koussa, the attending neurologist at Beirut’s Clemenceau Medical Center. “Some have substituted medicines with cheap Turkish or Iranian generics, which are still expensive because of the currency collapse,” he told the Blind Spot. Likewise, a local housewife informed me of the difficulty of buying Heinz Ketchup: “All you can buy are Turkish ketchups from brands you’ve never heard of.”

These efforts to intentionally offset price increases with circumvention will make monetary calculations more challenging.

This active manipulation of prices and products means you can’t just rely on a basket of goods and average prices to calculate inflation. Now, weight and size matter too. (…)

What shitflation (and shrinkflation) speaks to is the dissolution of our methodologies to calculate price increases. In that regard, it is an insidious phenomenon, reminiscent of the breakdown in price signalling that helped contribute to the fall of the USSR.

It also strongly implies that the price increases we hear about in newspapers and experience on the shop front are far from reflective of the true rate of inflation.

Rather than observing policy deficiencies offered by our politicians, we must first peer into data deficiencies caused by the shifting sands of our economies. It also leads us to a critical question; in a world that consciously manipulates data, how can we save large-scale data analyses? The solution, perhaps, is to integrate local, small-n findings that challenge the necessary assumptions held by large-scale analysis.