Indian Rupee Weakens as EM Exodus Continues, but Fundamentals Support INR Longer-Term

Image © Adobe Stock

- Rupee Continues sell-off on EM flight to safety and 'twin-deficit' fears

- Central bank inertia unsupportive but pressure mounting to act

- Strong growth and basic fundamentals means prospects for Rupee good

The Indian Rupee has been one of the worst hit currencies by the sell-off in emerging market (EM) assets and outflows into safer US bonds, but there are suggestions the weakness will ultimately have its limits.

Although the Rupee has weakened across the board it has fallen the most against the US Dollar which has benefited from increased inflows.

USD/INR is currently trading at a spot price of 71.695 at 12.15 B.S.T, on Wednesday, compared to a close of 70.805 at the end of last week - almost a whole Rupee higher.

GBP/INR is meanwhile up at 91.9705 from the previous week's close of 91.7290.

EUR/INR is trading at 83.1349 - up from a previous week spot price close of 82.1863.

Data out on Wednesday morning showed activity in the Indian services sector slowed down in August when the Nikkie services PMI fell from 54.2 to 51.5. Nikkei Manufacturing PMI data for the same period showed a similar slowdown when it was released on Monday morning.

The root cause of the Rupee's weakness is the perception that its economy is vulnerable due to a twin deficit, that is a budget deficit and current account deficit, which makes it reliant on foreign capital to meet its spending commitments.

The reliance on outside financing makes the Indian economy vulnerable to withdrawal of that external support as might be the case during an economic downturn or a currency crisis, as is currently feared.

The situation has been exacerbated in India by inertia from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) which could have intervened to support the Rupee but has chosen not to.

This is similar to the problem which led to the collapse of the Turkish Lira, because the Turkish central bank would not raise interest rates due to fears they would strangle off growth and, it is rumoured, pressure from President Erdogan.

"One problem is the RBI is not very concerned about the currency, they allow the Rupee to weaken they still believe that according to their own estimates of the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) the Rupee is not undervalued," says Nizam Idriss, head of strategy FI and currencies at Macquarie.

The REER is a fair value estimate of what a currency should cost ideally, based on trading data. It is is undervalued the assumption is that it will drift higher as is the case with INR.

Yet there are those who think that the Rupee's continuing devaluation will actually eventually lead to the RBI being forced to act in an emergency to support their currency.

There are several methods the RBI could use. The most common would be to raise interest rates, because higher interest rates attract greater inflows of foreign capital and help prevent outflows by recompensing investors more generously for the risk of holding Indian assets.

A stronger currency would help break the negative feedback loop which is driving the outflows and exacerbating the currency sell-off. In the case of the Rupee it is seen as the most viable and probable solution.

"The joker in the pack is the currency," says Sajjid Chinoy, Chief India Economist at JP Morgan. "I think the RBI October meeting very much comes into play and a strong GDP enables that."

India recorded 8.2% growth in Q2 making it probably the fastest growing economy in the world and this could provide an excuse for the RBI to hike rates in October.

"I think markets around the world are placing a premium on central bank orthodoxy and the MPC is not immune to that," says Chinoy.

Another possible method to help support the currency is for the RBI to use Open Market Operations (OMO), in which they would purchase Indian bonds.

This would help to soak up the extra supply created by the foreign investors ditching their Indian bonds and would both stabilise the falling price of bonds and the Rupee, says Kartik Goyal, a reporter at Bloomberg.

Recently the market has witnessed Indian bond yields rise to record highs. The yield is inversely proportionate to the bond price as it reflects the amount of compensation investors can expect to receive for holding the bond.

Higher yields are, therefore, another symptom of the exodus out of EM and back to safer US bonds, which underlies the fall in the Rupee, especially versus the US Dollar.

"The benchmark 10-year yield rose five basis points to 8.11 percent on Wednesday, the highest for a benchmark bond since Nov. 2014, while the rupee fell to a new all-time low of 71.96 per dollar," says Goyal.

The RBI would buy Indian bonds provide the domestic bond market with some relief and lessen the currency sell-off in the process.

"The RBI might buy sovereign debt worth about $50 billion in the six months to March 31, Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts estimated in an Aug. 7 note. It has made purchases worth about $4.2 billion so far," says Goyal.

The fundamental outlook for India is not as bad as for other EM countries caught up in the current crisis. India only really shares one main characteristic with the other vulnerable EM countries.

"The one profile that India has similar to the fragile EM economies is a twin deficit, which is one box ticked, but as for the rest, India looks healthier," says Macquarie's Idriss, who advocates trading long Rupee versus short Indonesian Rupiah as an expression of the Rupee's better fundamentals.

"If you think that this situation can continue without triggering systemic crisis in Asia you may want to consider going long Indian Rupee against Indonesian Rupiah. If things were to turn around and you get significant improvement the Indian Rupee could also outperform the Rupiah," says Idriss.

One major area in which the Indian economy is more protected than the Indonesian, according to Idriss, is that the RBI has set aside greater FX reserves with which to potentially meet any shortfall in financing if foreign investors were to pull the plug.

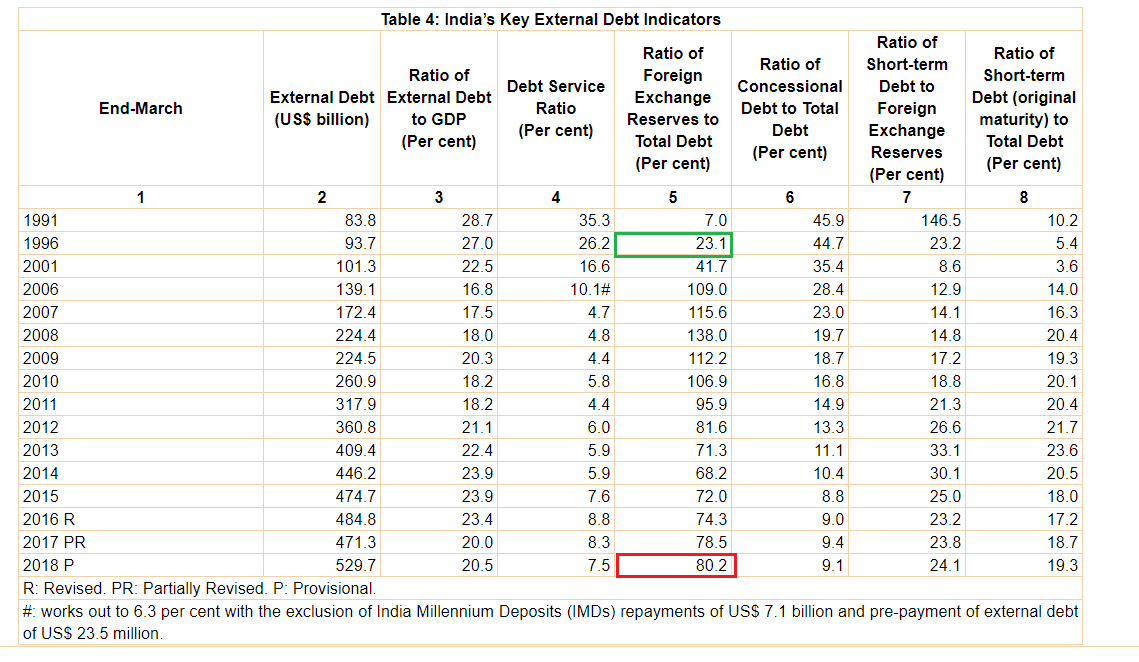

The RBI has enough reserves to cover 80.2% (red box) of its external debts, which is quite a high proportion. It compares with only 23.1% (green box) in 1996 during the Asian financial crisis when central banks lacked the adequate reserves to protect their economies.

The Indonesian central bank, on the other hand, only has enough reserves to cover about a third of its external debt of 352bn (2017), given reserves of only 118bn (July 2018).

Advertisement

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange for international payments by using a specialist provider to get closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank when providing currency. Learn more here