Should Pound Sterling Fear Corbyn's Labour Government? It Depends

- Written by: James Skinner

- The good, bad and ugly for Sterling under a Labour administration.

- Labour Party could be greater threat than Brexit say economists.

- Economic risks stemming from policy agenda tilted to the downside.

Image © Andy Miah, Flickr, reproduced under CC licensing

The resignation of Home Secretary Amber Rudd brings the question of government instability back to the fore for currency markets and economists are turning their attention to the potential implications for Pound Sterling posed by a Labour Party ascent to power.

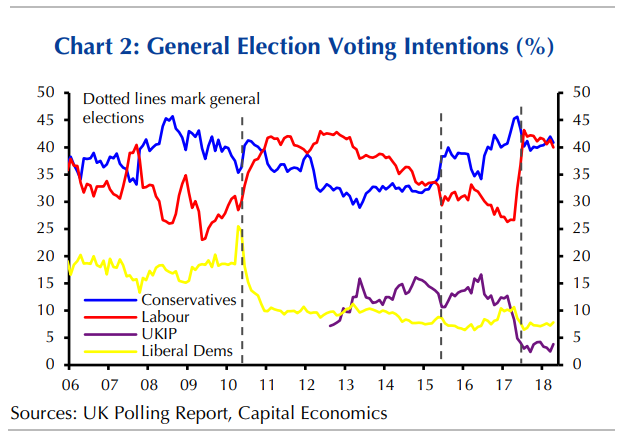

As is the case with Brexit, the nation's image in a Labour Party world is a difficult picture to paint, not least because every brush stroke requires an estimation of so many things that are highly unpredictable. But the growing risk of another election before 2022 and the Labour Party's improved polling performance under Jeremy Corbyn has pushed some economists to cross the Rubicon.

"Forget Brexit – the biggest thing that could happen to the UK economy in the next year or two is a change of government. In particular, we could soon be looking at a Labour government, with Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister. Cripes!" say Vicky Redwood and Andrew Wishart, economists at independent economic consultancy, Capital Economics.

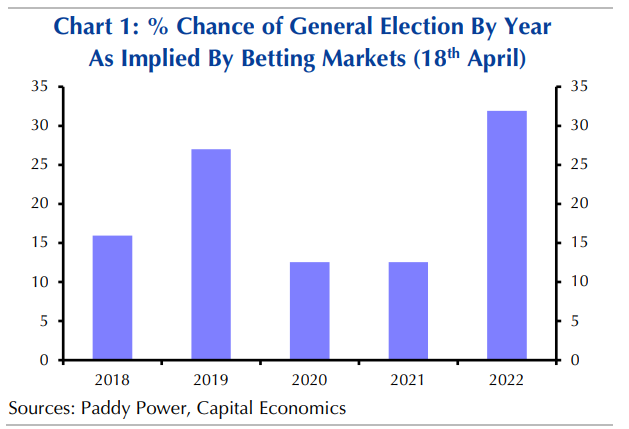

All of what follows will only matter if parlimentarians prove so unable or unwilling to deliver an exit from the European Union that a rethink is required or, for any other reason, another snap election is called. But Redwood and Wishart have flagged two main scenarios under which this could easily happen.

"Surely it would be madness to risk an election now, having got their fingers burnt last time, and when their standing in the polls has fallen further since? Nonetheless, there are a couple of ways in which an election could come about," Redwood and Wishart write in a recently published research note.

Local elections in May are widely expected to deliver a bloody nose to the ruling Conservative Party and, depending on how bad the actual drubbing becomes, there is some chance Prime Minister Theresa May could be forced to stand down and that a leadership contest would ensue suggest Capital Economics.

If this happens and a "Brexit hardliner" makes it onto the ballot there is a good chance such a person could become the next Conservative leader given the leave-leaning composition of the party membership. This could see pro-European Union MPs side with the opposition and force a vote of no confidence in the government, which would almost certainly mean another election.

"The govermnent faces a short-term test on 3 May in elections for 4350 local authority seats in 151 mainly urban areas," warns Philip Shaw, an economist at Investec Bank, in a recent note. "They do seem set to lose some councils, partly due to Brexit but also given a more general pro-Labour shift in the capital in recent years. The detailed picture though is highly nuanced and our feeling is that the Tories will hang on to a number of Councils."

A second scenario could see the government defeated by a coalition of its own MPs and the opposition later in the year when parliament votes on the European Union Withdrawal Bill and the Trade Bill. This too could lead to a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister and a subsequent general election.

An election can happen if two thirds of MPs in parliament vote for one, or if a no-confidence vote is not overturned within 14 days. Early indications are that, at the very least, Corbyn's Labour Party could mount a strong challenge to the Conservative Party's reign.

Understandably, some are attempting to quantify the potential economic impact of a Labour victory at the next election. This is no small feat, and is a far from an exact science.

"It is a fine balancing act for the Pound as a softening of Brexit plans could destabilize the government by alienating the Brexiteers and thereby potentially increase the risk of a Jeremy Corbyn led coalition government, which would be the worst outcome for the Pound. The adoption of less business friendly policies under a Corbyn-led coalition government would encourage a weaker pound even if the UK was much more likely to remain in the customs union," says Lee Hardman, a currency analyst at MUFG.

And with Monday's resignation of Home Secretary Rudd bringing government stability back to the fore it could be said the risk of an election is growing while Redwood and Wishart's research shows the economic risks tilted firmly to the downside in a Corbyn-led world.

Advertisement

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider to get closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank when providing currency. Learn more here.

The Good: Corbyn-Lite and a Soft Brexit

As the smaller leave-leaning side of the Conservative Party has found to its detriment, a parliamentary majority does not necessarily mean a government will have carte blanche over policy and legislation. Internal differences over policy can quickly scupper or restrain an electoral agenda and it is not unimaginable that government MPs ally themselves with members of the opposition to prevent policy proposals from making it onto the statute book.

"Obviously any of Mr Corbyn’s plans have to be passed by the House of Commons. And Labour’s MPs are, on the whole, considerably more moderate than Mr Corbyn. (Remember that a majority of them last year were planning to get rid of him!) Accordingly, Mr Corbyn might simply fail to get his more left-wing policies passed by government," say Redwood and Wishart.

There are still "moderate" faces on the opposition front and back benches, despite the Momentum insurgency that has given Corbyn significant influence over the shape of a future election line up. Assuming some of these make it onto the ballot in a future election, they could act as a moderating force in a Corbyn government.

"It is easy to promise all manner of things when in opposition. But when it comes actually to hammering out policy, paying for it and getting it passed through government, ambitions can quickly become curtailed," the economists write. "The Bank of England would also act as a constraint. In particular, a very expansionary fiscal policy would just be offset by higher interest rates."

The Labour leader has previously stoked controversy with proposals to remove the Bank of England's independence, to spur investment through "people's QE" that would see money created to pay directly for some £500 billion of infrastructure spending and to make university education "free".

This is not to mention Corbyn's many criticisms of capitalism and murmerings of policies that call into question the veteran socialist's commitment to private property rights.

Bank of England policy would be an important consideration for any Labour government given pledges to revive business investment across the economy. A policy approach that sees interest rates raised higher could easily scupper efforts to revive investment.

"Another potential constraint is Brexit. In particular, Mr Corbyn and his government might get so bogged down in Brexit that they simply do not manage to get anything else done. After all, this is what appears to have happened to the Conservatives," Redwood and Wishart write.

Capital Economics argues that, while there is every chance a Labour Party government may not come to power until after the Brexit process has been concluded, it could easily be the case that an election is forced before the UK has exited the EU and so much of the initial government term could be spent either dealing with or rolling back the process of extricating the UK from the bloc.

"The second reason not to worry about a Corbyn victory is that Labour’s fiscal plans belie claims that Labour would send the public finances to ruin. In fact, as long as Labour just followed the plans outlined in its manifesto, the economy would probably benefit," Redwood and Wishart write.

Contrary to popular belief, Labour has pledged to stick with the Conservative government's approach to the budget, which has been to balance the books after removing "investment spending" from the equation. Higher day-to-day spending would be funded by higher taxes while increased borrowing would be for the purpose of investment.

"This extra spending would obviously leave public sector borrowing higher than under the Tories’ plans, but the difference would not be large," the economists note.

Capital Economics calculations suggest that, under a Labour government, 2018 borrowing would be equal to around 2.7% of GDP. This is less than 1% more than the 1.8% of GDP targetted by the Conservatives.

"So on the face of it, there would be no reason for bond investors to run for the hills. After all, bond yields remained low even when public sector borrowing was running at much higher levels than Labour is planning. And the sanguine market reaction to the fiscal stimulus announced by US President Trump in February is potentially reassuring," Redwood and Wishart write, noting there is no shortage of investment projects and the interest rate environment remains favourable.

Furthermore, in the event Brexit hasn't been concluded if and when Labour capture Number 10, events in 2018 have called into question the Labour Party's commitment to delivering any kind of exit from the European Union. Particularly after the February flip-flop that saw Labour seeking "a customs union" with the EU that would look remarkably like the current one.

That, and the composition of the shadow cabinet, make a so called "soft Brexit" much more likely under a Labour government. This would of course be good for Pound Sterling and, as far as conventional wisdom goes, the economy too.

The Bad: Debt Splurge

While there may be scope for moderating forces in parliament to counter the more radical tendencies of a Corbyn premiership, to the extent there may utlimately be very little difference between a Labour and Conservative government, there are also "reasons to worry".

"We pointed out earlier that Labour plans to raise borrowing by a relatively small amount," say Redwood and Wishart. "But there is a big question mark over whether Labour would manage to raise as much money from its planned tax rises as it claims."

Much of Labour's claim to a budget-neutral manifesto rests on the assumption it will be able to offset higher government spending through increased corporation taxes or new taxes such as the "excessive pay levy".

The party claimed in its latest manifesto that it would raise some £49 billion of revenue from new or increased taxes but Capital Economics cites estimates by the Institute for Fiscal Studies that suggest, at best, the proposed levies would raise only £41 billion.

"Of course, if Labour’s policies resulted in stronger GDP growth, then borrowing would come in lower than currently forecast," say Redwood and Wishart. "But if Labour’s policies ended up resulting in a weaker economic performance than currently forecast, then borrowing would be higher, and borrowing as a share of GDP doubly so."

The market response to Labour policies of increased government involvement in the economy, anti-business tax plans and heavy handed financial regulation is what will determine the ultimate cost or benefit of a Labour administration. Should economic activity slow as a result of the Labour policy mix then the party's spending plans could soon become problematic.

"If tax receipts disappointed, either because of optimistic assumptions in the manifesto or a weaker economy, Labour could just tighten its belt in response. But can we really imagine Labour, the anti-austerity party, doing that? No. Accordingly, borrowing would probably take the strain," say Redwood and Wishart.

The danger of this is that if markets become sceptical of the government's commitment to sustaianable public finances then bond yields could rise sharply, which would raise the cost of borrowing and mean that more taxpayer funds have to be spent on debt interest.

This could also have adverse consequences for the Pound if markets came to doubt the long term solvency of the government.

The Ugly: Corby-Max

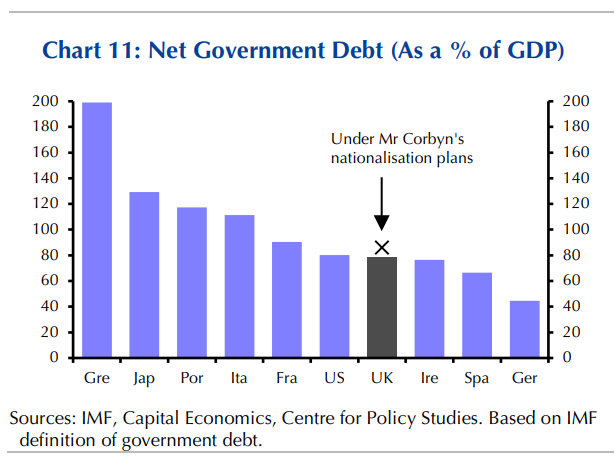

Another pillar of the Labour manifesto that could pose a challenge to the party's fiscal credibility, and that may upset markets, is Corbyn's nationalisation plan. This would see water, energy, rail and postal services nationalised, at great cost to the public purse, if implemented to the letter.

"In some ways, Labour’s nationalisation plans are not that radical," say Redwood and Wishart. "Nonetheless, there are still some concerns. The first is the degree to which current shareholders would be compensated."

When challenged in the past over the potential costs of its nationalisation plans, shadown chancellor John McDonnell has floated the idea of buying out existing shareholders at "a discount", raising the spectre of an effort to cheat current investors out of their assets.

Estimates from the Centre for Policy Studies, which are at the higher end of the range for all those produced, have previously suggested Labour's nationalisation plan could cost up to £176 billion.

"Although this would be subject to legal challenges and might not succeed, it would send a bad message to investors in UK assets. Second, there is a big question mark over Labour’s ability to run these companies better than the private sector," the economists write.

Commuters on the national rail network will know more so than those who have avoided the pleasure that some industries are not always more efficient, and service quality note always improved, when they are placed in the hands of the private sector. But there is little evidence to suggest that government could do a better job.

In fact, with rail travel being a case in point, the Network Rail organisation responsible for all of Britain's railway infrastructure is itself a publicly owned company. What's more, its fingerprints have been found all over many of the current system's failures.

For instance, the faulty signalling equipment that is a frequent cause of delays is itself operated by Network Rail and so too are the rail stations that lack capacity to support larger trains capable of carrying more passengers and therefore, of enabling seating to be provided to all travellers.

"Even if Labour did manage to keep overall public borrowing under control, the economy might nonetheless suffer from the big expansion in the size of the public sector," Redwood and Wishart warn.

Labour's nationalisation plans and other manifesto pledges would see government revenues as a share of GDP rise to their highest level since before the Thatcher years of the 1980s. Although the evidence around what a large public sector means for an economy is not clear cut.

The ailments of the French economy are well known yet what is often less spoken of is the success of the Nordic countries, which have Europe's largest public sectors as a portion of GDP but some of the continent's highest levels of GDP per head. In short, the latter are some of the continent's better off countries.

"However, this is partly because they have combined a big welfare state with free market capitalism. This is not what Mr Corbyn is suggesting," say Redwood and Wishart. "The public sector in the Nordic countries is successful in part because it introduces elements of the private sector (e.g. school vouchers) – precisely the opposite of Mr Corbyn’s “the state knows best” philosophy."

This simple comparison of course ignores differences in the direction of travel between France and the Nordics, with French government spending as a share of GDP having remained substantial during recent years while the Nordic countries, althogh still having a high level of government involvement in the economy, have been reducing the scale of state expenditure.

"A further reason to worry about the impact of a Corbyn-led government on the economy is the potential effect of his anti-business policies," warn Redwood and Wishart. "Some of Labour’s measures look significantly more onerous for businesses, especially those which boost labour costs."

Labour has repeatedly pledged that, if elected, it will raise taxes substantially. At present corporation tax is due to fall gradually from 1% to 17% over coming years but Labour's most recent plan would cancel this and eventually restore the 26% corporation tax rate that prevailed before 2011.

The party has also pledged large increases in the minimum wage and to repeal Conservative legislation that restricts the power of trade unions.

"Other things equal, employers’ labour costs would rise by £1bn per year under the Conservatives, and by £14bn per year under Labour – equivalent to 3.5% of firms’ annual gross profits. And the cost would be even bigger if it had a knock-on effect on workers higher up the pay scale," Redwood and Wishart warn, citing estimates produced by the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

This would be the result of Labour Party plans to raise the minimum wage to £10 per hour before 2020, which is far and above the £8.75 "Living Wage" pledge made by the Conservative Party. These additional costs could have a substantial impact on firms' profitability.

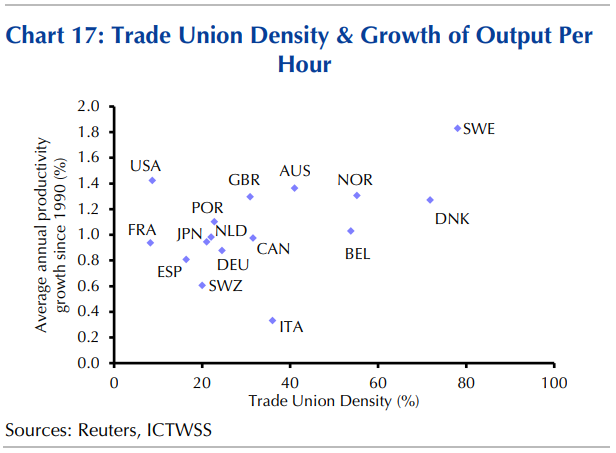

"Admittedly, the effects of trade unions on the economy are much debated and in recent years, there has been no obvious relationship between trade union density and productivity growth. Nonetheless, trade unions are often seen as acting as an obstacle to productivity-enhancing improvements, making it harder to hire and fire workers and boosting wages above market rates," Redwood and Wishart warn.

"What’s more, even if each of these policies in isolation is not too damaging for business, cumulatively it all adds up. Put it all together and you can see why profits and investment would not fare well under a Corbyn government," Redwood and Wishart warn. "Indeed, you could hardly expect anything different given that Mr Corbyn’s whole philosophy hinges on reducing the profits share in order to boost labour’s share of income."

Another aspect of the Corbyn campaign and policy platform perceived as a threat to the UK's economic performance is the Labour Party attitude toward the financial services industry, which contributes close to 10% of all UK tax revenues and employs a large number of workers.

"We doubt that Labour’s policies would be drastic enough to prompt a sudden mass exodus of financial institutions from London. Nonetheless, coming on top of Brexit, they could be enough to tip the balance for some firms," Redwood and Wishart write.

Labour has pledged to reverse previous reductions to the bank levy and introduce a new tax on all debt and equity trades, which sounds a lot like the "Tobin Tax" floated and then abandoned by the European Union. The City would also bear the brunt of Labour's personal tax policy, which would see the higher rate of tax increased to 50% and the threshold for this reduced from the currenct £150k to just £80k.

"There has to come a tipping point where tax rates start to have a significant adverse impact on work incentives and therefore undermine economic growth and tax revenues," the economists write.

This is a salient point because, as was highlighted by Redwood and Wishart, the Conservative government may already have reached the limits of revenue-raising taxes. After all, David Cameron introduced a higher 50% rate of tax back in 2010 only it neither raised any more tax revenue nor prompted a fall in tax revenue.

"The fact that the introduction of the 50p rate in 2010 neither raised nor dented revenues significantly suggests that this marks the peak of the so-called Laffer curve (i.e. the revenue-maximising rate of tax) and that significant tax rises above this would start to become selfdefeating."

Last but not least, all of this assumes that Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party stick to their manifesto and do not take an election victory as an invitation to pursue a more hardline socialist agenda.

"Having waited decades to get a socialist government in power, Mr Corbyn and friends would surely find it hard to resist the opportunity to introduce a radical socialist agenda," Redwood and Wishart warn. "Of course, this would mean overcoming the political constraints we mentioned earlier. But this would be possible if the next general election saw an increase in the share of Labour MPs that are sympathetic to Jeremy Corbyn’s agenda."

Should a Labour government pursue a more hardline and anti-business agenda than even the party manifesto suggests is likely, then the implications for Pound Sterling could be pretty bleak. So reports the shadow cabinet is already planning how it would deal with a possible run on the Pound may come as little consolation to those companies and households that have to buy foreign currency on a regular basis.

Advertisement

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider to get closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank when providing currency. Learn more here.