Fiscal Rules: Three Fixes for a Broken System from Oxford Economics

Above: The Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt poses outside 11 Downing Street with the Red Box, alongside the other Treasury ministers, before he delivers the Budget to parliament. 10 Downing Street. Picture by Simon Walker / No 10 Downing Street.

Current fiscal rules lack credibility, impose scant debt discipline, and allow governments to game the system. Oxford Economics proposes three solutions that would help cut government debt, boost growth, and reduce the scale of austerity that the next parliament will be forced into.

Last week's Budget offered a perfect demonstration of the flaws in the current fiscal rules and the extent to which politicians have become willing to game the system.

The Chancellor implemented an immediate tax cut, despite the public sector net debt-to-GDP ratio being projected to rise over the next five years, and maintained very tight spending assumptions without any underlying detail on how they will be implemented.

Labour seem to be committed to a similar approach.

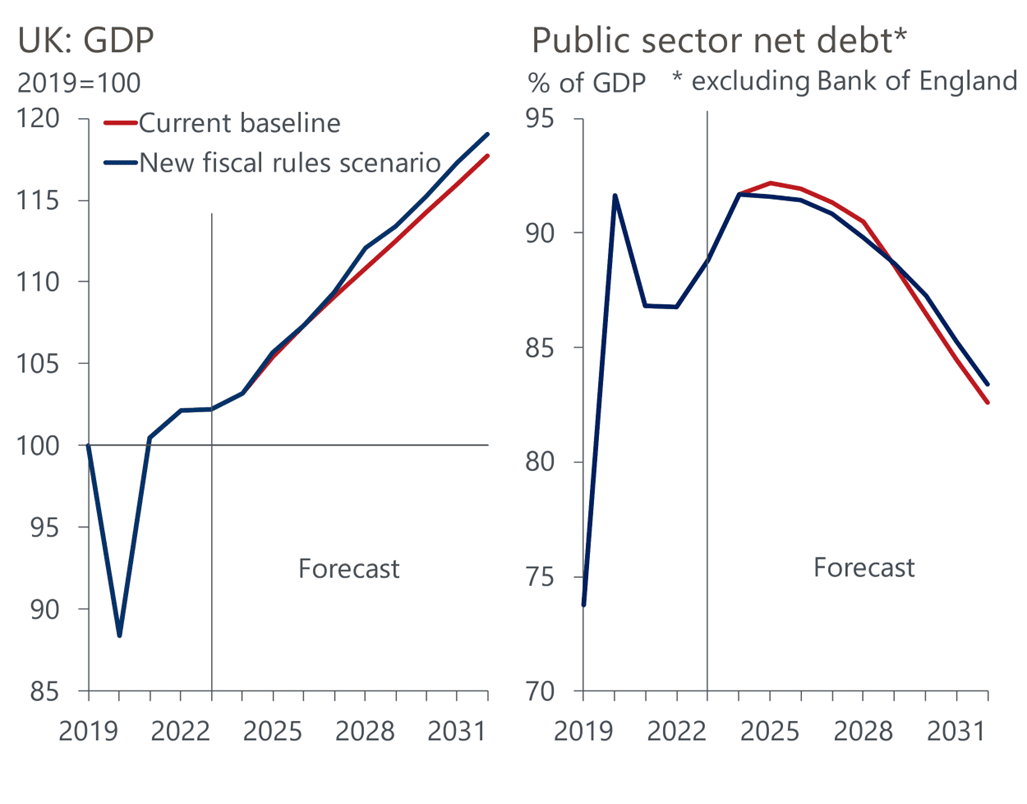

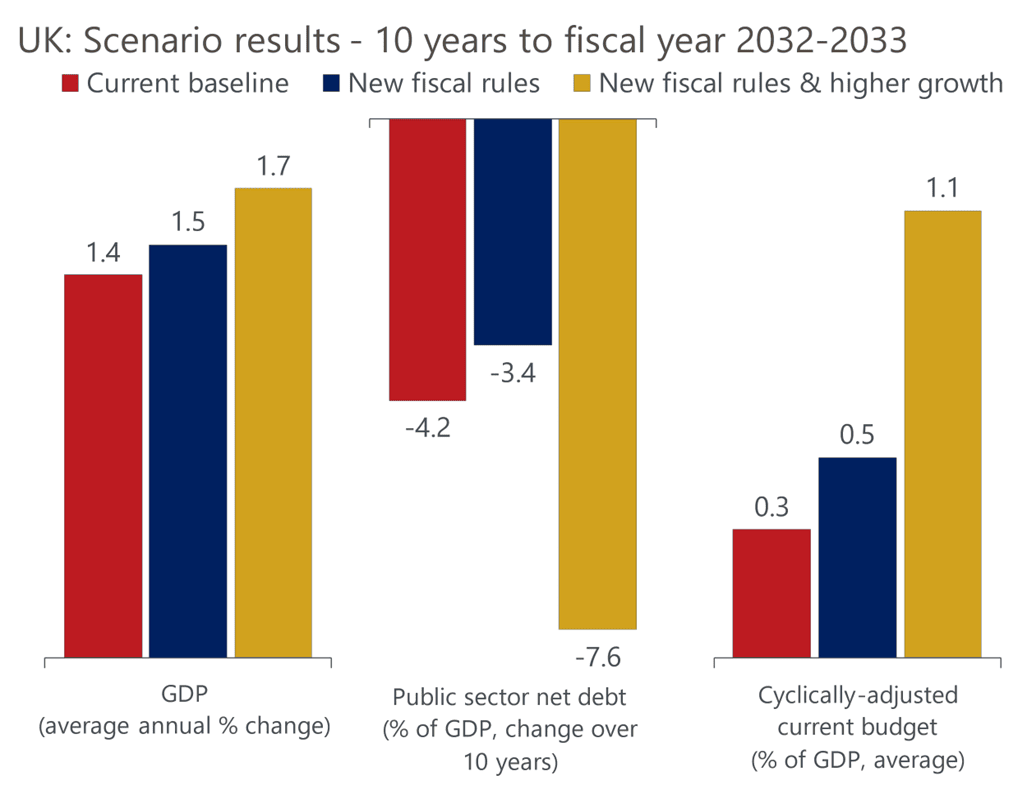

We think there's a better way and set out here our proposals for overhauling the fiscal rules and implementing a more growth-friendly policy mix. Simulations using our Global Economic Model suggest adopting these would yield stronger economic growth while lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Better fiscal rules would result in stronger growth and keep the debt ratio falling

Sources: Oxford Economics, Haver Analytics

The core problems with the current fiscal rules

The dysfunctional state of fiscal policy is partly due to the choice of fiscal rules and partly a function of how the government has shaped policy within these constraints. The core problems are:

A rolling five-year target imposes little fiscal discipline.

The target of ensuring debt is falling in year five takes no account of the starting point, and there is no compulsion to achieve targets in the first four years. Also, there are no corrective mechanisms for past underperformance, which means as the horizon always remains five years ahead, fiscal plans can be loosened over time.

So, for instance while the Office for Budget Responsibility currently projects that public sector net debt (excluding the Bank of England) will rise by more than 4ppts as a share of GDP over the next five years, the government still complies with its fiscal mandate because the debt ratio falls by 0.3ppts between years four and five. What's more, despite the debt ratio being projected to rise, the Chancellor was able to loosen policy at the last two fiscal events.

Tax and spending plans are treated asymmetrically.

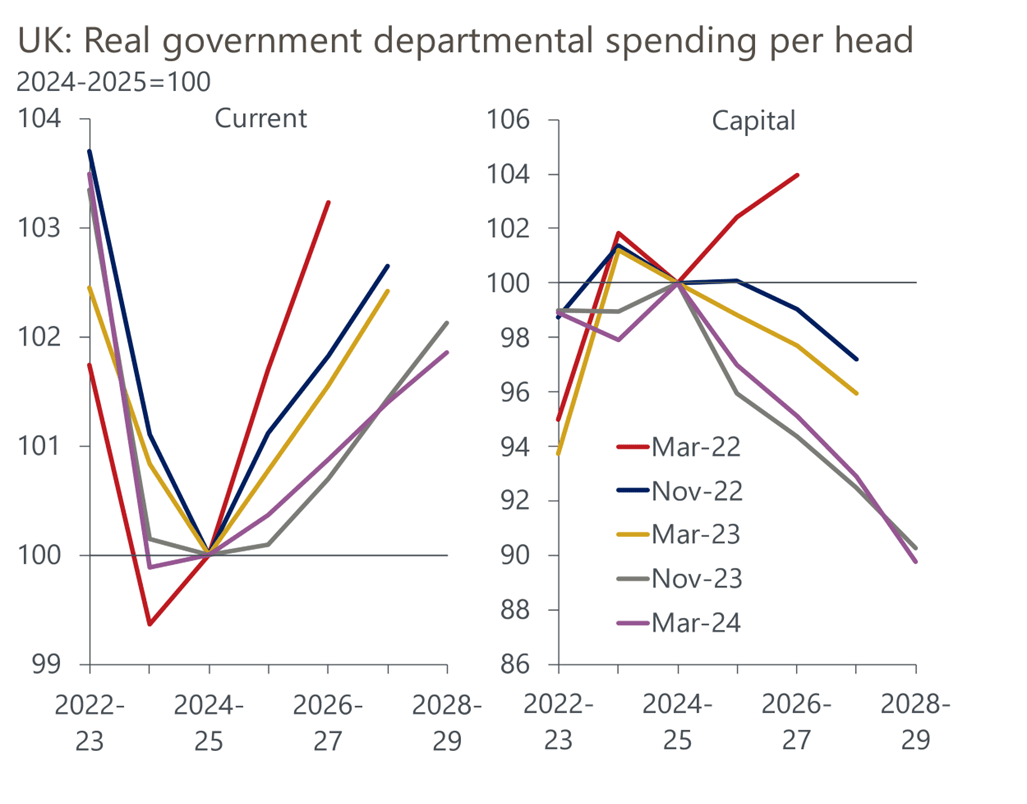

The government announces specific plans for tax changes, but there is no compulsion to present similar detailed departmental spending plans. At present there are no detailed plans on spending for the final four years of the OBR's forecast horizon, just cash totals. As recent fiscal events demonstrate, this creates an incentive to assume ever greater spending restraint (Chart 2). Given the increasing funding demands from key public services such as health and defence, the current plans imply unfeasibly large real terms spending cuts for unprotected departments

Chart 2: The government has progressively squeezed future departmental spending

Source: Oxford Economics calculations using forecasts from OBR

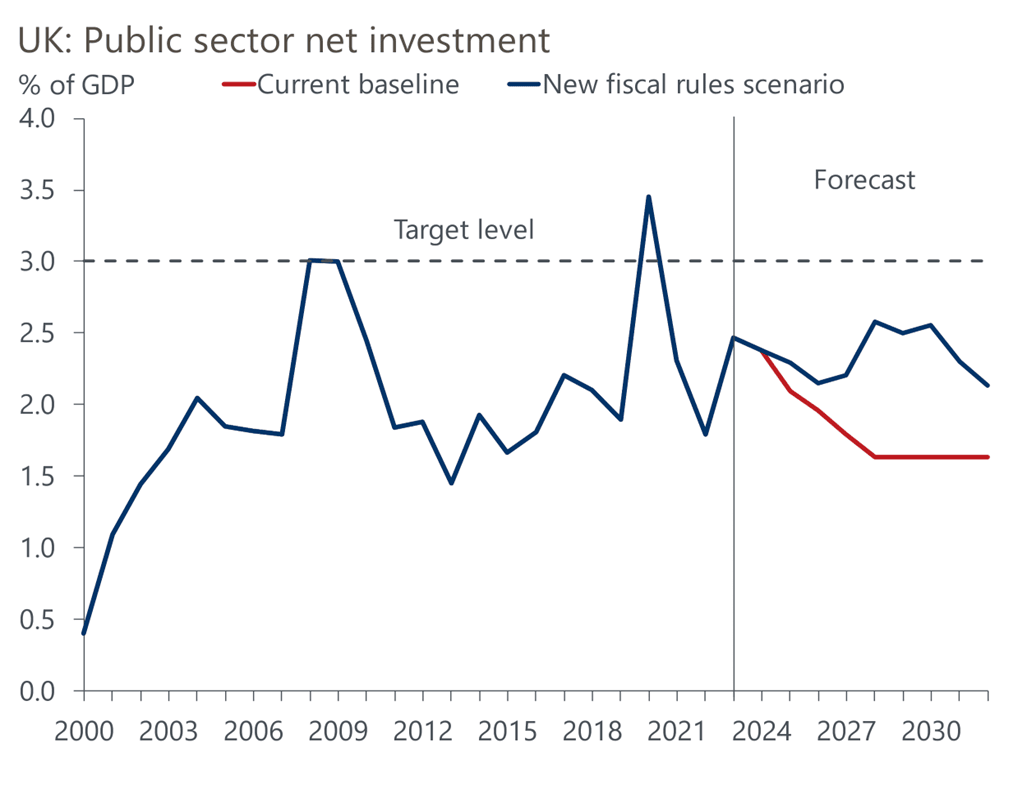

Investment is discouraged.

The deficit rule targets public sector net borrowing of less than 3% of GDP in year five. This effectively treats capital spending the same as current spending, ignoring the evidence that the long-term economic returns from public investment are high. Experience suggests governments find it much easier to cut investment plans than reduce day-to-day spending commitments (Chart 2).

The UK has one of the lowest public investment-to-GDP ratios in the OCED in recent years and current plans show public sector net investment falling to just 1.7% of GDP in 2028-2029. Since the start of the century investment has been lower in only one other fiscal year.

Asset Purchase Facility losses cause distortions.

Though the debt measure excludes the Bank of England, it does include the cost of the Treasury indemnifying the BoE for losses when it sells gilts held in the facility. This makes a material difference to the Chancellor's room for manoeuvre – the OBR's latest forecast assumes just over £20bn of losses on gilt sales in year five of the forecast horizon (2028-2029). But as soon as the BoE finishes selling gilts, these costs will cease. We argue that it's not desirable to leave fiscal policy so open to the heavy influence of one-off effects, particularly given the impact is so uneven from year-to-year.

The current situation also creates an incentive for the Treasury to influence the Monetary Policy Committee's decisions on the pace of APF rundown, potentially eroding the Committee's independence.

The detail of the fiscal framework has gone through a number of iterations since the OBR was formed in 2010, so these design flaws have been present to varying degrees throughout that period. But we think the current rules are the most flawed. The issues have been exacerbated by Chancellors who have been willing to squeeze the headroom against the rules, leaving no margin for error or changing circumstances.

More recently, the proximity of the general election has increased the incentive to delay fiscal consolidation and rely more on unspecified future spending cuts to make the sums add up.

We propose three changes to the fiscal rules

Our proposals aim to impose greater fiscal discipline while providing room to increase capital spending. The three key changes are:

1) Reduce the time horizon to three years from five.

This will strengthen the link between the fiscal rules and the government's fiscal plans, while also providing some degree of flexibility to adapt to unexpected shocks.

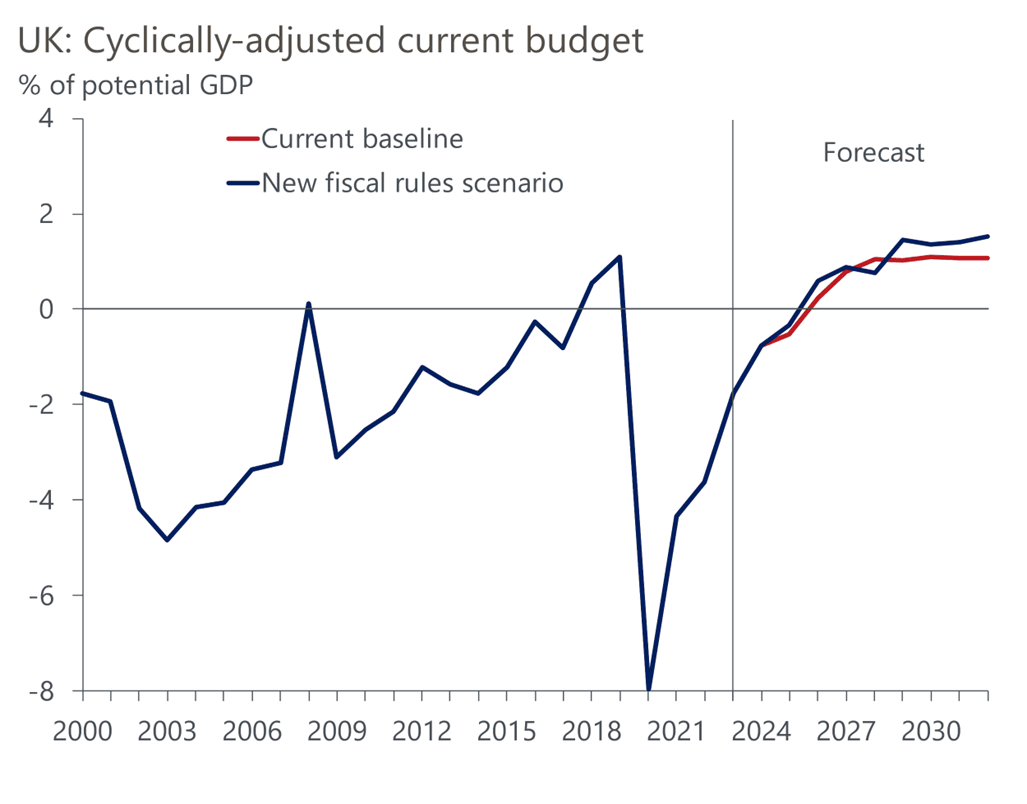

2) Change the deficit rule so that it targets a balance or surplus on the cyclically-adjusted current budget measure, rather than public sector net borrowing.

This would take investment out of the deficit rule. We recognise that this change places greater importance on the OBR's forecast for the output gap. But in most circumstances the practical implications would be limited as the OBR tends to assume the output gap is closed, or at least close to zero, over a three-year horizon.

3) Remove the impact of APF losses from the net debt measure.

This would ensure policy options are not constrained by one-off factors that are largely outside of the government's control.

We also recommend two changes to the way the government approaches fiscal policy to boost the credibility of its plans and create a more stable backdrop:

Spending reviews

These should be conducted annually when the forecast horizon rolls forward, so that all future spending assumptions are backed by a department-by-department breakdown.

This process, used by most businesses, would bolster the credibility of the assumptions. It would also reduce the risk of a repeat of the current charade both of the main political parties have to maintain that they will implement the scale of post-election spending cuts that the fiscal plans assume.

Only one policymaking event per year, apart from in exceptional circumstances.

The OBR would continue to publish two forecasts a year, but the second would be an interim update to check that current fiscal plans remain on track. This would discourage the short-termism that has blighted fiscal policymaking in recent years and create a more stable backdrop for business planning.

Indeed, a government with a coherent fiscal strategy should be capable of setting out its plans for taxation and spending at the start of a parliament, and then making only minor adjustments year-by-year.

Last, while we propose a three-year horizon for the fiscal rules, we recommend that the OBR extends its forecast horizon to ten years. This would indicate if existing policies are consistent with achieving fiscal targets on a sustained basis. It would also recognise the importance of supply-side policies on potential output growth and the public finances. Forecasting the impact of policies on public sector net worth would also help in this regard.

We also recommend changes to the fiscal policy mix

At the same time, we recommend recalibrating the approach to fiscal policy, respecting both the proposed fiscal rules and the political backdrop. We suggest a focus on two priorities. First, supporting economic growth and improving the UK's decaying infrastructure via higher levels of public investment.

We calculate the proposed changes to the fiscal rules would permit around £170bn worth of extra investment over the next decade compared with our baseline forecast (Chart 3).

Chart 3: The new fiscal rules would offer scope to boost investment

Sources: Oxford Economics, Haver Analytics

This would mean public sector net investment averages 2.4% of GDP over the next ten years. While a vast improvement on current plans, it's short of the 3% of GDP level that we think the UK should target. That target should still be achievable over a longer time horizon.

The second priority is funding public services. Recent polling by YouGov found that more than twice as many respondents believed that the government should prioritise funding public services over personal tax cuts. So we think a modest increase in the tax take would be politically feasible to fund higher current spending.

For example, we estimate a combination of reversing the cut in the rate of National Insurance contributions announced in the Budget, implementing Labour's suggestion of levying VAT on private school fees, and introducing tiering on bank reserves would raise around £15bn a year (0.5% of GDP).

This could be recycled into higher departmental spending. As well as addressing public concerns, higher spending on public services could generate positive feedback to the economy, particularly if increased spending on healthcare helps to reverse the downward trend in participation due to long-term sickness.

Our modelling shows stronger growth outcomes and falling debt levels

To analyse the impact of these changes we ran a simulation on our Global Economic Model. We applied the new fiscal assumptions to our baseline forecast 'ex ante' and then solved the model to encompass any second-round effects from the policies.

Our scenario shows the level of GDP would be 1.1ppts higher than our baseline forecast at the end of our ten-year horizon (Chart 1).

The new fiscal assumptions represent a net loosening of the fiscal stance, particularly towards the end of the decade – under the current rules, APF losses are a particularly important constraint on policy in this period. Given that higher levels of public investment account for the bulk of this loosening, there would be boosts to both demand and supply. So while inflation and interest rates rise above baseline levels, the improvement in productive potential means that activity is permanently higher.

The scenario shows that policy always remains compliant with the new fiscal rules. The decline in the public sector net debt-to-GDP ratio is similar to that in our baseline forecast, while the cyclically-adjusted current budget remains in surplus throughout (Chart 4). Indeed, there is sufficient headroom against both the debt and deficit rules that, as time goes by, there would be scope for some of the surplus to be recycled into higher current or capital spending.

Chart 4: The current budget remains in surplus from year three onwards

Sources: Oxford Economics, Haver Analytics

Supply-side reforms could drive a further improvement

Our modelling looks solely at the improvements that could follow from new fiscal rules and a better policy mix. It does not include any improvements in potential output from other policy changes, such as planning reform or increased spending on education.

We published our plan for boosting potential output before the March 2023 Budget. The seven recommendations were:

- Make the supply-side a priority and draw in external experts to formulate specific policy measures.

- Boost relations and trade links with the EU.

- Reduce childcare costs.

- Increase education spending, emphasising STEM subjects.

- Lift public investment to 3% of GDP and reset the fiscal rules.

- Increase housebuilding, implement planning reform, and overhaul property taxes.

- Raise the retirement age.

In the three fiscal events since we published our plan, the government has delivered on most of our recommendations for reducing childcare costs. But there's been little progress on the other six proposals.

As we've demonstrated in this report, there would be clear benefits in terms of growth and fiscal outcomes from overhauling the fiscal rules and boosting public investment, in particular.

If the next government can make tangible progress in the other five areas, the improvement in the fiscal dynamics could be greater still. We've run an additional simulation that layers stronger economic growth on top of our new fiscal rules. This simulation assumes that advances in areas such as planning reform boost total factor productivity and add 0.25ppts a year to potential output growth over the next ten years.

The results suggest that stronger growth would result in larger surpluses on the cyclically-adjusted current budget measure to the tune of 0.6% of GDP per year over and above our new fiscal rules scenario, with a much larger fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the ten year period (Chart 5).

Chart 5: If the government could boost potential output growth then fiscal outcomes would improve

Source: Oxford Economics

The stronger fiscal outcomes in the higher growth scenario would offer the government much greater policy flexibility. It might opt to further increase the funding of public services.

It could increase public investment closer to our target level of 3% of GDP, hoping to further take advantage of the virtuous circle where stronger public investment boosts potential output growth, which generates stronger fiscal outcomes. Or it could prioritise a faster fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio to provide more fiscal space to react to future shocks.

But the key message from our scenarios is that if the fiscal rules, policy mix, and supply-side policies are well aligned then they will produce much stronger growth and better fiscal outcomes.