Here's Why Britain's "Wage Squeeze" Might Not Last

- Written by: James Skinner

Britain's "wage squeeze" is unlikely to last but those who are looking to substantiate a position of caution toward the UK economy should keep a close eye on the housing market.

The worst of the post-referendum wage squeeze could now be behind British households, says one economist, with more moderate inflation and steady pay growth likely to mean a resumption of real income growth takes hold early in the new year.

Although the long term growth potential of the UK economy has been hindered by the outcome of the referendum, which is a consensus view among economists, inflation presents only a passing risk to consumer spending according to Kallum Pickering - a senior economist at Berenberg.

Instead, those looking to substantiate a position of caution toward the UK economy would do well to take a closer look at the housing market, which has a historically important link with household spending and where price growth is slowing.

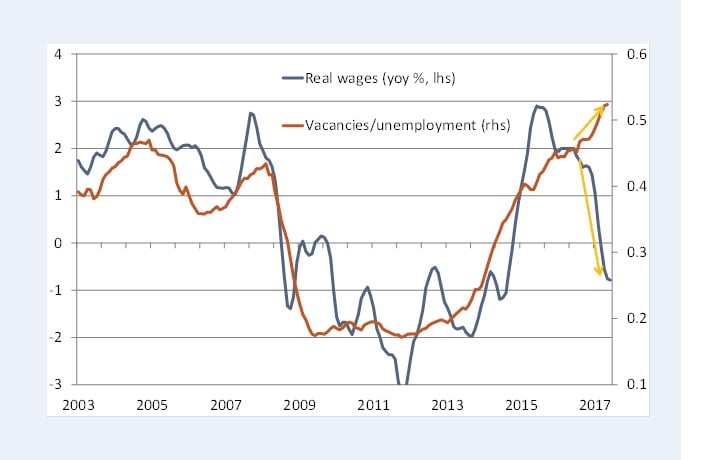

“In the long-run, real wage growth tends to track the degree of tightness in the labour market. But the shock Brexit vote has temporarily forced a gap in this relationship,” says Kallum Pickering, senior UK economist at Berenberg, in a note sent to clients Monday.

Pickering flagged the continued fall in UK unemployment during recent months that, when combined with a rising rate of vacancies and continued growth in nominal wages, points toward a recovery of real incomes during the months ahead.

With the Pound to Euro exchange rate down more than 17% since the night of the referendum and the Pound to US Dollar rate down 13.6%, consumer price inflation reached close to 3% in June after import costs were pushed up sharply.

“The major sources of upward pressure to the headline inflation rate seem to have peaked. It will take a few more months for these cost pressures to fully pass through. We expect headline inflation to peak at 2.9% in Q3 2017,” says Pickering.

Falling real incomes and lower rates of business investment have formed the base for many a dire prediction of UK economic growth over the coming quarters.

Lower rates of business investment were among the reasons cited by IHS Markit Monday for the UK construction PMI having fallen to a year long low in August.

This is while the uncertainty factor, which is noteworthy in the context of stalled Brexit negotiations, has frequently been cited as a likely source of a possible slowdown in the labour market during the coming months.

“The argument touted by some pundits that firms will be reluctant to raises wage amid Brexit uncertainty simply is not backed by the data which signals labour demand is at a record high,” says Pickering. “Vacancies signal firms’ demand for labour. When vacancies rise, it signals that firms want to increase their workforces. And implicitly, that firms are willing to raise their wage bills.”

Instead of being concerned with any possible hit to the economy coming from real incomes, investors, traders and economy-watchers would do well to keep a closer eye on the condition of the UK housing market says Pickering.

Housing has typically had a large influence over consumer spending, with households leveraging their balance sheets when prices rise and cutting back sharply when prices fall.

Many will remember then-Chancellor George Osborne’s unveiling of the Help to Buy home purchase scheme in 2013, its subsequent effect on the housing market and the economy - which been at risk of a double dip recession up until the summer of 2013.

“Given the strong links between household balance sheets and the housing market, it is hard to imagine a scenario where a nationwide fall in house prices did not trigger a sharp contraction in aggregate household spending,” Pickering concludes in his note. “While a nationwide decline in house prices is not our base case, recent softness in the London market serves as a warning that this is the key risk to watch.”

A Monday note from the RBS economics team, led by chief economist Stephen Boyle, chimed with that of Berenberg economist Pickering in that it also offered a slightly more chirpy appraisal of the current UK economic backdrop than has been seen in much recent punditry.

Beneath the headlines, last week’s data depict a reasonably sunny economic landscape across the Eurozone, the US and, even the UK,” RBS says.

The bank flagged a multiyear record for private sector capital raising during July as a reason to be optimistic about the economy’s near term prospects.

Private companies tapped bank lenders for a total of £5 billion during the month and leant on the bond market for another £3.5 billion, despite data showing that the average business in the UK has a healthy net cash position on its balance sheet.

“The Bank of England has been expecting that investment would grow to offset weaker consumers’ spending and to capitalise on export opportunities. Maybe it’s happening now,” the RBS team noted.

This is while, according to the latest Bank of England lending data, the “air is seeping very slowly out of the consumer credit bubble.” Recently a key source of concern for policy makers, credit card borrowing grew at its slowest pace for six months in July, up 8.9% year over year, while borrowing to finance car purchases and other large ticket items also slowed.

The benign view is that we have rationally used credit to smooth consumption because higher inflation has temporarily squeezed our spending power. In this world, borrowing will slow as income growth returns. Let’s hope that’s correct.,” the team says.