The Indian Rupee Outlook is Darkening

The Rupee may be about to fall as doubts increase about Indian Economic fundamentals in spite of a recent thumbs up from Moodys.

At the start of 2017, the Indian Rupee was expected to be one of the top performers in Asian FX, yet its poor performance over the last three months has brought into question that view.

Most recently the currency's failure to react to the good news that premier rating agency Moody's raised India's credit rating to Baa2 is said to reflect underlying investor concerns about weak spots in the economy.

Doubts about the currency have reached a point where RBC Capital Markets, for one, has placed the Rupee (INR) on probation.

"These (three) underlying dynamics leave us cautious about our long-held view of INR outperformance within the region for the coming year. We will reserve judgment for now, but the next three months will give a much clearer picture," says RBC Capital Markets Head of Asia FX Strategy Sue Trinh (our brackets).

So what is causing all the concern, and why isn't the Rupee rising as much as analysts thought it would?

The positive view of INR came out of a major campaign of reforms enacted by the Modi government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which were seen as beneficial to the economy.

One of these reforms was the implementation of an Indian VAT (Goods Service Tax or GST), to harmonise and simplify sectoral and regional goods tax differences - another the demonitisation of large currency notes, which encouraged the still largely cash-based economy to open bank accounts or risk notes held becoming worthless.

Yet whilst these reforms and others were seen as positive, they did not go far enough in some areas such as banking reform, according to Tring, and they didn't remove certain inherent vulnerabilities in the Indian economic model which remain a risk to the outlook for the Rupee.

Still In Hock

The first of these 'inherent vulnerabilities' is India's relatively large debt burden, which is currently 72.0% of GDP, and the highest in the region bar Japan's.

Whilst the government is trying hard to bring its budget deficit down so it doesn't have to borrow so much, its efforts have stalled recently, and Trinh is not very confident they will resume.

"Consolidation has seen the budget deficit narrow from 6.1% of GDP in 2012 to 3.5%. But there is now a real possibility that India misses its target of 3.2% in 2017/18 and 3% in 2018/19 due to farm loan waivers by some States, potential stimulus measures by the Central Government ahead of 2019 elections such as the bank recapitalisation plan and rising oil prices," says the RBC analyst.

Whilst increased stimulus and bank recapitalization could raise inflation and increase the chances of the RBI increasing interest rates, which would be positive for the INR (foreign investors like higher interest rates which lead to higher inflows and increased demand for the Rupee), heavy debt's in the long-term will be negative.

A high debt burden is a blight on a country's ability to invest, modernise and develop infrastructure, and this will eventually prove negative for the Rupee because it will turn off potential foreign investors seeking to purchase a piece of the Indian economy, whether it be in the form of shares in Indian companies, Indian bonds, hard assets, land property, businesses.

The reduction in these inflows, also known as Foreign Direct investment or FDI will lower demand for the currency, weakening it.

Worsening Trade

A major factor in currency valuation is a country's balance of trade - a nation which exports more than it imports, normally sees its currency rise from increased demand, yet in the case of India the balance is tipping in the opposite way, favouring a rise in imports rather than exports, and consequently increased weakness for INR.

The main reason has been a rise in costly gold imports used by Indians in great quantities during wedding ceremonies, an increase in the price of oil, which India must import a lot of, and India's inability to capitalise on the electronics export boom in the region.

As a consequence, it is importing considerably more than it exports.

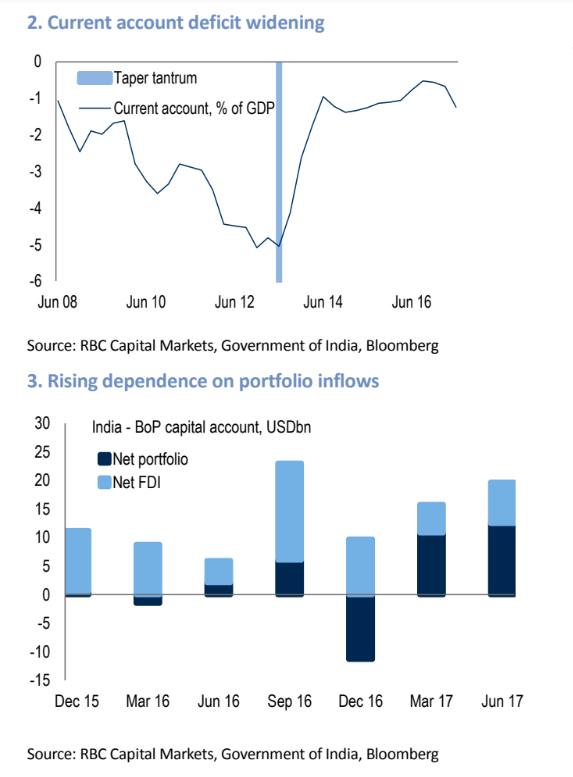

"But in Q1 2017/18, the deficit widened sharply to a 4-year high of 2.4% (USD14.3bn), due primarily to a surge in gold imports and the increase in crude oil prices (petroleum and crude products are over a third of India’s import basket), while export growth has stalled on the back of the strong INR and India’s poor leverage to the regional upswing in electronics exports, which contributed just ~2% of India’s export basket in H1 FY17," says Trinh.

The trade deficit is nothing new, but the reason why analysts were not as worried about it before is that it was offset to a considerable degree by increasing demand for Indian financial assets from foreign investors keen to join the rising stock market and from foreign funds buying Indian sovereign bonds.

Yet India has become increasingly reliant on demand for its financial assets - or Portfolio flows as economists call them - to balance the overall flow of money in and out - which economists call the Current Account.

A reliance on demand for its financial assets from foreigners in order to balance its Current Account deficit is a major vulnerability.

"In Q1, net portfolio investment was USD12.5bn, compared to USD2.1bn last year. These flows are vulnerable to a reduction in global liquidity/turn in global risk sentiment and investment limits – foreign investors have used up almost all of their eligible quotas to buy Indian bonds," says Trinh.

Bank 'Recap'

The third and final drag on the Rupee is expected to be from the current perilous state of Indian banks.

Their problems are similar to those of the Eurozone periphery - especially Italy - where banks have on their books a high proportion of loans which are not being paid backed - or as 'non-performing loans' (NPL) in jargon.

The problem with this is that it reduces banks willingness to lend, even to viable customers, because of the risk that these new loans too may become non-performing and will have to be written off as a loss.

As a consequence, the economy cannot grow.

The government's answer is to pump money into banks - or recapitalise them as its called - so they have more money with which to write off the bad debts or lend out in new loans.

"The government recently announced INR2.11trn (~USD32.5bn) for bank recapitalisation over two years to clean banks’ books and help revive investment growth," says RBC analyst.

Yet, Trinh has concerns about the government's recapitalisation programme, which offset the programme's rhetoric.

For a start the extra money will have to be borrowed, thereby increasing the country's debt which is already worryingly high (see above).

Secondly, many of the banks with the worst portfolios of NPL's are already state-owned, creating the potential for 'moral hazard', which means there may be a lack of incentive to make the best use of the recapitised money.

Finally, it's not enough:

"Fitch estimates the government will need twice as much more capital - at least USD65bn - by March 2019 to address the system-related risks as well as meet the stricter capital requirements of Basel lll."

Unique Strengths

it is probably worth considering some inherent and unique offsetting strengths the Indian economy possesses which could support the outlook for INR.

The Indian economy is the fifth fastest growing economy in the world - behind Bhutan, Ethiopia, Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire and is now growing more rapidly than China.

It has a more diversified economy than most in Asia with a strong services sector and manufacturing, making it more resilient during sector specific downturns.

It has relatively well-educated populace a relatively high proportion of whom speak English, still probably the lingua Franca of the world.

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider by getting closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank for international payments. Learn more here.