Seasonalty: Will the Euro Weaken in December and Strengthen in January?

Goldman Sachs tackle the question of whether or not the Euro will decline in December and recover in January - based purely on seasonality.

'The Lady Tasting Tea' is the name of a famous experiment carried out by one of the father's of statistics, Ronald Fisher.

Fisher knew a lady who claimed she could accurately tell the difference between whether a cup of tea had been made with the milk added after or before the tea had been poured, based solely on its taste.

Given there appeared to be no basis for her knowledge - tea tasted the same either way - Fisher decided to design an experiment to put her assertion to the test.

The experiment is one of the classics of statistics and the principle's which govern Fisher's conclusions are still used in data analysis, especially of financial markets to this day.

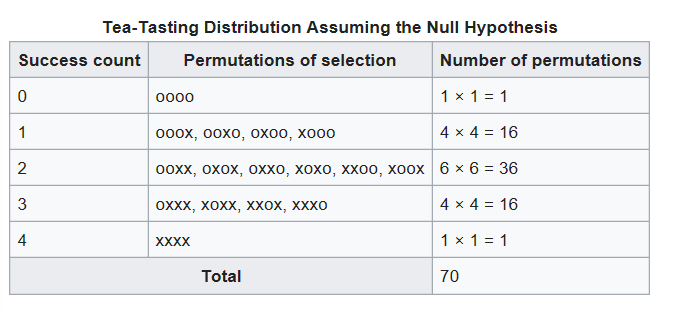

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Fisher prepared eight cups of tea, four with the milk added after the tea and four with the milk added before the tea was poured, then he invited the lady in and asked her to taste them and classify which of the cups of tea belonged in the two different types.

Fisher determined beforehand that in order to have a high degree of confidence that the lady had a special ability she would have to correctly classify all eight cups - getting only six out of the eight right, despite it being the next best result, would not be good enough.

Rumour has it that the lady did, in fact, get all eight right.

Did this, therefore, mean that she possessed a special ability?

Fisher concluded that she probably did but he couldn't be 100% sure, because there was a possibility that she might have chosen the correct cups out of luck, yet the chances of her doing so were too small to be significant.

There were 70 possible combinations in all, in which she could have classified the eight cups but only 1 was the right one - and she chose that one, suggesting, to a high degree of probability that it was not luck but skill which determined the outcome.

The reason getting six of the eight right, for example, would not good enough was because there were too many combinations in which that might be achieved, introducing too high a chance that pure luck had played a part in the result.

The experiment is particularly pertinent to the forecasting of financial markets where it is often difficult to correctly distinguish between whether an accurate forecast has been arrived at by skill or simply by luck.

Euro Seasonality

In a recent paper entitled "G10 Seasonality: Count us Sceptics", Goldman Sachs Analysts Michael Cahill and Lorenzo Incoronato also put to the test assertions made by forecasters claiming that certain currencies - such as the Euro - follow predictable seasonal patterns.

For example, it has been argued, that the Euro has a strong tendency to strengthen towards the end of the calendar year and then to weaken in January.

In order to test the Euro hypothesis Cahill and Incoronato design an experiment which measures monthly changes in the EUR/USD (and other major crosses too).

If seasonality exists, EUR/USD should consistently rise in December and fall in January.

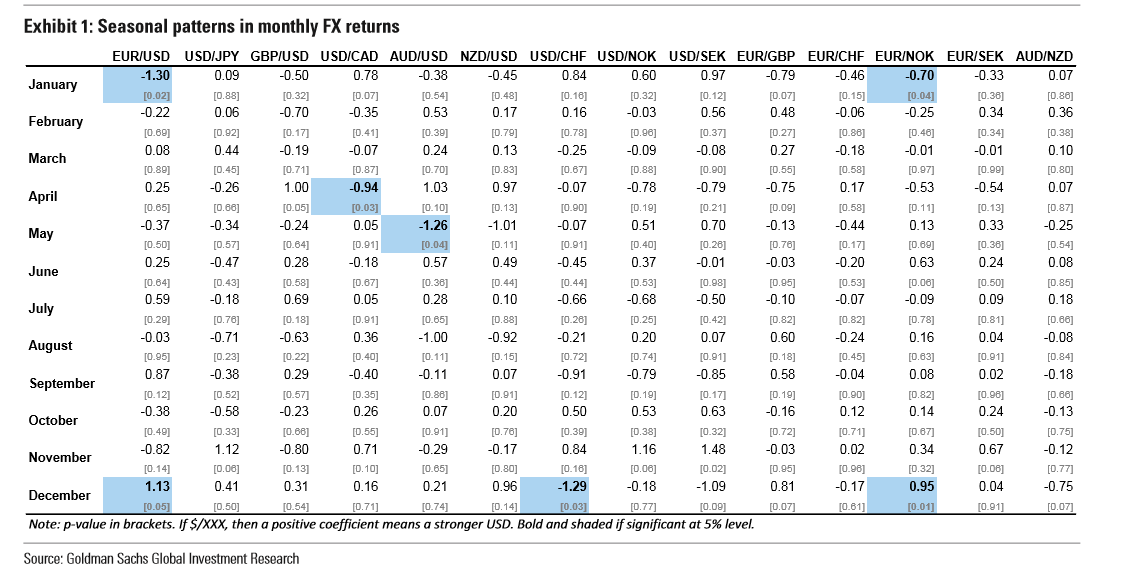

The results of their experiment are presented in the table below, although it only shows the 'coefficient' for the different months, which is a complex statistical concept, nevertheless, the important thing to understand is that the further the number is away from zero (either higher or lower) the more significant the result.

To make it more easily understandable, Cahill and Incoronato highlight the months showing a high degree of seasonality - to an acceptable level of confidence - in light blue.

The results appear to show that there is a tendency for the Euro to rise in December and fall in January as both these months are highlighted.

The same pattern appears to exist in EUR/NOK.

The results from the first experiment back up the theory of seasonality in the Euro.

But how confident can we be that they are not simply as a result of blind chance?

In the Lady Tasting Tea experiment, the lady needed to get eight out of eight for Fisher to be confident she had a skill and it wasn't just luck.

In fact, this translates into a 98.6% probability she chose the cups correctly because she meant to, not because she got lucky.

Nevertheless, this is still well above the accepted scientific minimum confidence threshold of 95%, which is the threshold Goldman Sachs use in their experiment on seasonality.

The highlighted results, therefore, have a 95% confidence attached to them, that they were caused by seasonality rather than randomness.

Yet despite this Cahill and Incoronato's conclusions from the data are rather dismissive:

"EUR/USD does show some seasonal tendency around the end of the year (with EUR strengthening into year-end and reversing in January). The same pattern is also true in EUR/NOK....All of these results are broadly consistent with our previous research, however, in general, it appears that EUR seasonality has declined. This underscores the instability and poor fit of these estimates."

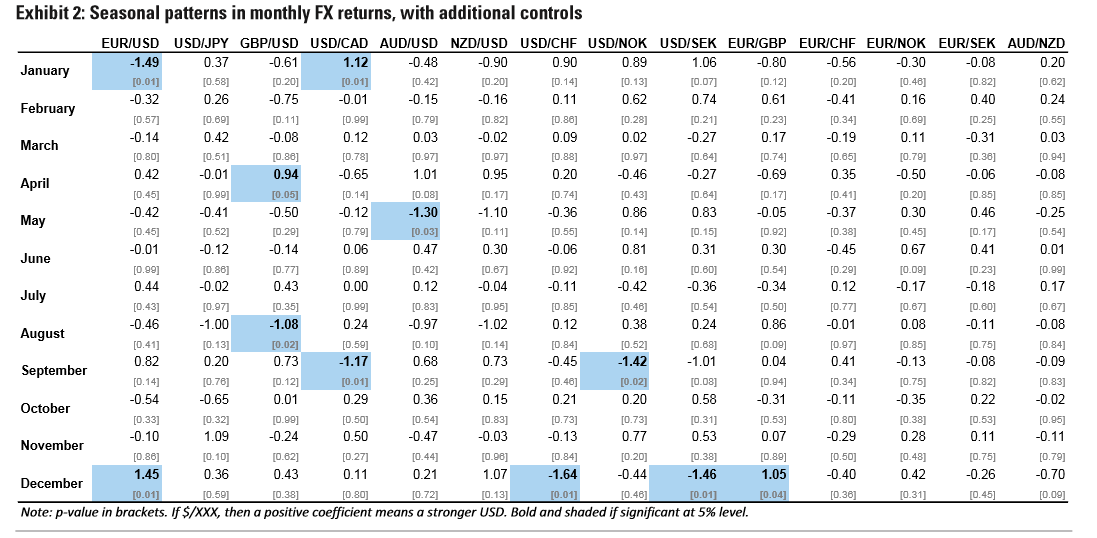

The next experiment Goldman's Cahill and Incoronato devise to test seasonality is more rigorous as it tests not just whether there is evidence of seasonality but whether it is more important than other "more traditional drivers of FX returns such as interest rate differentials."

Interest rate differentials are premised on the principle that currencies with higher interest rates tend to appreciate against those with lower rates.

This is due to the fact that international investors tend to transfer money from lower interest to higher interest rate jurisdictions, thus the currencies of the latter tend to appreciate.

When Cahill and Incoronato run their test with the added variable of rate differentials, they come up with the results below, which still show significant seasonality in January and December under EUR/USD, although not for EUR/NOK anymore.

Yet again, however, Cahill and Incoronato are rather dismissive of the results:

"Even after adding these additional control variables, we still find evidence of EUR/USD seasonality around the turn of the year, but the pattern no longer extends to EUR/NOK or EUR/SEK (Exhibit 2). And once again, we see that the coefficients in many cases are not stable between these two methods, further demonstrating that seasonality does not fit the data well."

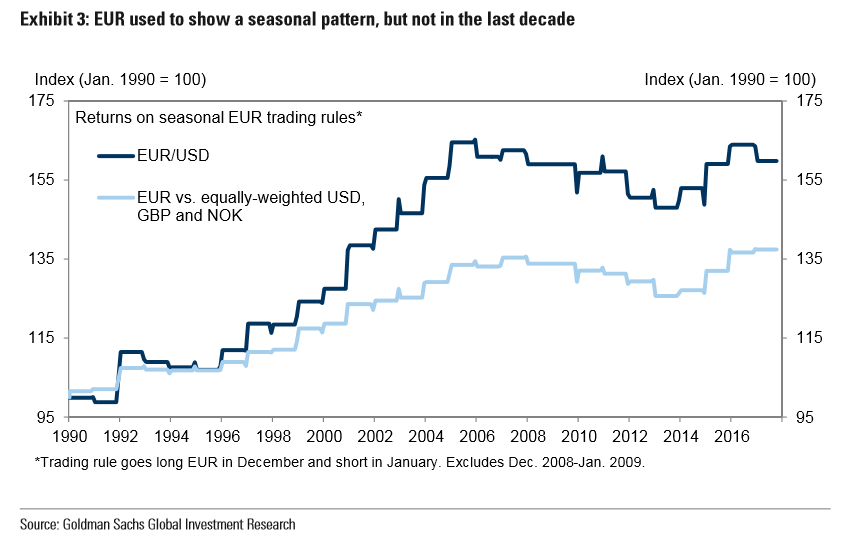

In their final experiment, Cahill and Incoronato test EUR/USD alone for end of year seasonality but adopt a slightly different approach using trading rules instead.

They construct a trading strategy which buys in December and sells in January and then chart the profits from the strategy.

If there is a high correlation then profits from the strategy should reflect this by rising in a steady upwards line on the chart.

The results are shown below and show that whilst the strategy gave consistent profits up until 2005 it has broadly gone sideways since then, indicating that the seasonal effect seems to have worn off since 2005.

Conclusion

Despite their experiments seeming to indicate seasonality, to some extent exists for EUR/USD in line with the theory that the Euro strengthens into year end and then weakens in January, the experimenters remain highly sceptical of any claims to seasonality in FX pairs.

They argue that the results are probably just incidences of random patterns.

In an echo of the Lady Tasting Tea, they argue that if a currency shows strength (or weakness) in December consistently for five months in a row - like the Euro - it might look like there is a seasonal cause behind it when actually it's is a purely random streak.

Although on its own a sequence of five strong December's would be rare in a purely random sample (equivalent to tossing a coin the same side five times in a row which is 6.25%), if taken together with nine other currency pairs the chance that at least one of them will show a run of five in a row becomes much higher at 6.25% x 10 = 62.5%, which is probable.

" But as we start to add more coins, the probability rises substantially that at least one of them will hit a streak. In fact, if we flip more than 10 separate coins (or consider more than 10 FX crosses), it is actually more likely than not that one of them will show the same side five times in a row."

They conclude that:

"As the universe of crosses expands, it actually becomes probable that we will observe at least one “lucky streak” at any given time (Exhibit 4). We find this a much more plausible explanation for what otherwise looks like unexplainable seasonality, and this sort of randomness can only be sorted out over a very long time horizon."

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider by getting closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank for international payments. Learn more here.