How Negative Interest Rates Could Work at the Bank of England

- Written by: James Skinner

-

- GBP outperforms after BoE seems to reject negative rates.

- GBP not heard last of it as MPC still mulling subzero rates.

- Eventual decision may see negative rates on 'term funding.'

- Not Bank Rate; could be less GBP negative than perceived.

© Adobe Stock

Negative interest rates are unlikely at the Bank of England (BoE) if the latest remarks from Governor Andrew Bailey and the foreign exchange market's response to them are anything to go by, although the matter is not decisively settled and at least some derivation of the controversial policy could yet be implemented.

Sterling was bid higher on Jan. 13 after Bailey told the Scottish Chambers of Commerce on Tuesday that there's "lots of issues" with using negative interest rates as a policy tool.

This was after Sylvana Tenreyro, an external member of the BoE's Monetary Policy Committee and professor at the London School of Economics, said in an online presentation on Monday that it's "not too late" to implement them and Bank Rate could "theoretically" be cut below -0.75%.

Bailey's Tuesday remarks dispelled a cloud of gloom that had hung over the Pound through the early days of the New Year when a renewed national 'lockdown' led to speculation in some parts about a possible later decision to push the BoE's benchmark for borrowing costs below zero later this year.

"Pain would be acute for building societies, which are legally required to source more than 50% of their funding from retail deposits. Given these impacts, it is doubtful U.K. lenders would reduce interest rates on new loans much, if at all," says Samuel Tombs chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics in a recent research piece. "By contrast, the MPC can step up the pace of QE swiftly and without harmful side-effects."

Above: Pound-to-Dollar rate shown at hourly intervals and alongside Pound-to-Euro rate (blue).

Central banks traditionally used interest rates to influence the level of lending in an economy in response to rising and falling inflation pressures, but with many including the BoE having struggled to lift borrowing costs from their post-financial crisis floor over the last decade, they've increasingly been running out of room to help economies in hard times.

With benchmarks like Bank Rate, which was cut to a new low of 0.1% in March 2020, having sat close to zero for years some central banks have become increasingly reliant on other tools in order to incentivise the faster economic growth thought to be necessary for attainment of their inflation targets.

Quantitative easing, which enhances the transmission of low benchmark rates by forcing down the government bond yields that get baked into all rates charged across the economy, has become increasingly popular but this particular tool may be nearing its limits at the BoE and other central banks.

{wbamp-hide start}{wbamp-hide end}{wbamp-show start}{wbamp-show end}

Bond yields have been close to zero for years also, thanks to a combination of low Bank Rate and ever larger volumes of quantitative easing, but the BoE has relied on the policy enough now for it to have become the owner of almost half the British government's stock of outstanding debt.

"Broadbent failed to mention the issue in the text of his speech on ‘how Covid has impacted the spending habits of households’. That said, Broadbent did later comment that if negative rates are used he would want them to bolster lending," says Jane Foley, a senior FX strategist at Rabobank, referring to an intermittent Tuesday speech by MPC Member Ben Broadbent. "While GBP has found support on yesterday’s remarks from Bailey, very little new news has been provided on the negative interest rate front."

When the nine-member Monetary Policy Committee voted to cut Bank Rate to 0.1% last year it also agreed to lift the BoE's quantitative easing target from £435bn to £645bn, but since then that target has been further increased to £895bn and an amount equivalent to around half of 2020's anticipated UK GDP.

But soon after that March rate cut, BoE staff began working on analyses of how a negative interest rate policy might actually be implemented and have since asked lenders to prepare for such an eventuality.

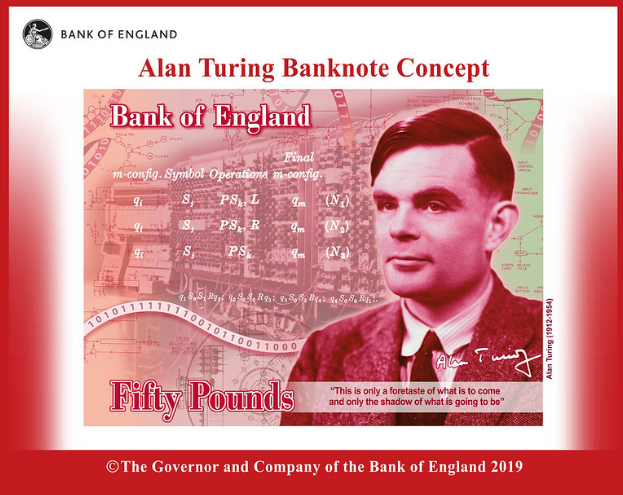

Source: Bank of England.

The BoE still needs a way to meet its 2% inflation target - traditionally done by influencing the level of lending to the real economy - which is why the markets and Pound Sterling have probably not yet heard the last about negative interest rates despite this week's remarks from Bailey.

Furthermore, and with some of the bank's rate setters including Sylvana Tenreyro and Michael Saunders having cited the benefits that were seemingly achieved by other central banks elsewhere, it's not possible for opponents of the policy to say that it's completely without merit.

But this doesn't mean either that concerns harboured by Bailey and other staff couldn't be addressed in a way that still enables the BoE to harvest the benefits espoused by Tenreyro and Saunders.

Taking a leaf from the European Central Bank's book may help to do both.

"The interest rate applied on all TLTRO III operations outstanding over the period from 24 June 2021 to 23 June 2022 will be 50 basis points below the average interest rate on the deposit facility prevailing over the same period, and in any case not higher than -1%," says the ECB in a December 10 announcement. "The deposit facility rate is currently -0.5%. The lending performance threshold that needs to be met in order for a participating counterparty to attain the minimum interest rate on TLTRO III..."

Since cutting its main interest rate to zero and deposit rate (the one it used to pay to lenders who park cash with it) below zero the European Central Bank has increasingly turned to what it calls targeted-long-term-refinancing-operations or so-called TLTROs. These are direct loans from the ECB, to commercial lenders, made at super cheap interest rates and with the specific intention of encouraging increased lending to "the real economy."

Source: Pantheon Macroeconomics. Market pricing as of January 11.

Commercial lenders who meet predefined targets for increasing their loan books are able to borrow money from the ECB at rates lower than its main interest rate and in some cases, rates which are even lower than the deeply negative -0.5% deposit rate that it now charges lenders who park cash with it. The Bank of England already uses so-called TLTROs, although it calls them "funding for lending" or "term funding" schemes instead. And it just hasn't gotten quite as far as applying negative interest rates to them yet.

"A negative Bank Rate would squeeze lenders’ net interest margins, as deposit rates already are at zero, whereas the income from floating-rate loans, many of which are contractually linked to Bank Rate, would decline," warns Pantheon's Tombs. "We expect the MPC to enhance its Term Funding Scheme, so that banks can access four-year funds from it at a negative interest rate, instead of just at Bank Rate. This would require the Treasury’s sign off, as the APF would be loss-making, but we doubt that this is an insurmountable hurdle."

Rate cuts are always a form of subsidy and negative rates are no different only if the BoE was to apply negative rates to its TLTROs or term funding schemes instead of Bank Rate itself, it'd be ensuring that this subsidy is charged to the accounts of the bank and its policymakers rather than to those of private commercial lenders, investors and household savers.

Most importantly, this approach might have more scope to provide Sterling with a tailwind of support rather than an additional burden to carry, because the cost of stimulating the economy into a more palatable performance would fall on the bank and overall taxpayer rather than on investors and household savers.

Source: Pantheon Macroeconomics.