How Much Will the Euro Rise As the Economic Recovery on the Continent Takes Hold?

The fiscal-cocaine of cheap borrowing has sustained the recovery in the Eurozone but what are the implications for the single currency?

The Eurozone is likely to continue its recovery as long as the cost of borrowing remains low, says a leading economist.

Recently the economy of the Euro area has gone from strength to strength and it is expected to continue to do so, says the economist.

This year the Eurozone is expected to grow by 2.3%, easily beating consensus estimates of just 1.3%, according to Commerzbank Chief Economist Dr. Jorg Kramer, and the rate of growth is likely to continue steadily for some time yet.

"The arithmetic shows that the recovery could go on for another three years," says Kramer.

Nor is the region's damaged periphery being excluded. Here too respectable growth rates are being achieved.

"Even Italy, long the euro zone’s problem child, will post 1.5% growth this year. France is heading for even slightly higher growth, at 1.7%," the economist adds.

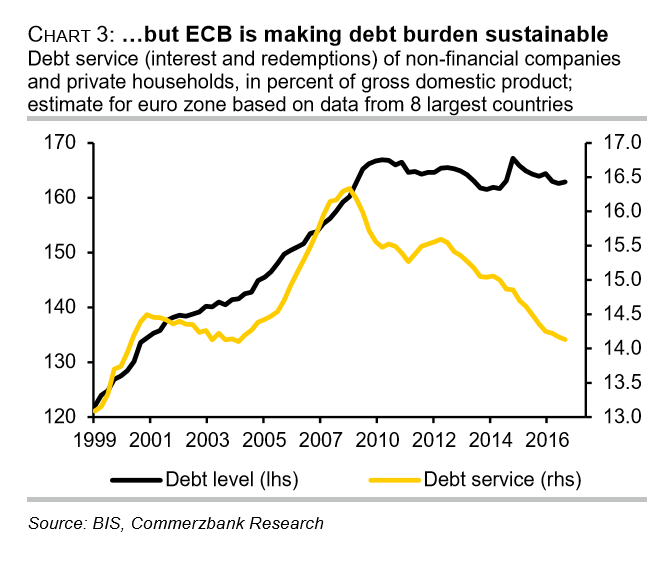

Kramer puts the growth down to lower borrowing rates in the region, which are at historic lows.

The low-interest that borrowers have to pay when they take out loans means financing is cheaper for businesses and individuals, who can take out more debt. Both factors are currently stimulating demand in the economy.

The low-interest loans available in the Euro area are the result of the European Central Bank's (ECB) current monetary policy.

The ECB is the 'bank for banks' in that it lends to high street and commercial banks, who then lend to the public at a slight premium.

It sets the interest rates payable on its loans, which tends to influence interest rates all through the region's financial system.

If the ECB raises interest rates then the rise is usually passed on to customers by their banks - and vice-versa if the ECB cuts rates.

What if Rates Go Up?

Assuming Kramer's hypothesis is correct, however, would it not also make the Eurozone economy vulnerable if the ECB decided to raise its interest rate?

It would, but, says Kramer, this is highly unlikely to happen.

Firstly, central banks normally only raise interest rates to combat inflation and fulfil their mandate of price stability, and there is no sign that inflation is substantially on the rise in the Euro area.

One of the main drivers of inflation is rising wages. These usually rise when there are fewer unemployed, as employers have to offer higher salaries to attract workers from the dwindling pool of available talent.

In the Eurozone, the unemployment rate has fallen quite a lot in recent time but, at 8.9%, it is still nowhere near low enough to lift inflation.

In other economies with much lower levels of unemployment, such as the US (4.1%), Australia (5.5%), and the UK (4.3%), the impact on wages has been limited. This suggests the link between the two is now more tenuous than before.

The reasons for this are complex but Bank of England governor Mark Carney has hypothesised recently that it probably has something to do with a mixture of globalisation - which has flooded some market places with more workers -, increased automation and technological innovations such as the internet.

A further reason not to expect the ECB to raise interest rates is the high levels of debt - both public and private - in the region, which would become increasingly expensive to service were the ECB to raise interest rates.

Italy, in particular, is susceptible, with Kramer describing it as a kind of "tripwire" because of its high sensitivity that results from a very high public and private debt burden.

"Italy is more sensitive than most to the problem of high private and public debt. In addition, it is the largest sovereign debtor in the euro zone, so that economic problems in Italy would have a massive impact on other countries in the union," says Kramer.

Euro May Be Loser

From an FX viewpoint, Kramer's analysis of the causes of the recovery may not on the surface support a rise in the Euro, for they are based on the expectation that the ECB will continue to keep interest rates low - which is Euro-negative.

Interest rates are a major driver of currencies with higher interest rates leading to a stronger currency and vice versa for lower interest rates.

Higher interest rates strengthen a currency by attracting greater inflows of foreign capital drawn by the promise of higher interest returns, and this boosts demand for the host currency.

A continuation of the strategy of low-interest rates, therefore, will deny the Euro of support from higher interest rates.

So if the recovery has been driven mainly by the cheap borrowing and this continues for several years, as Kramer expects then the Euro may be limited in its capacity to appreciate.

Trade Could Be Supportive Factor for Euro

Although the culture of low-interest rates envisaged by Kramer may not support the Euro the currency may yet not fall.

Other factors could still support the Euro according to analysis from Strategist Lefteris Farmakis at investment bank UBS, who posits the Euro is set to rise due to its positive trade record.

Farmakis draws on a model which estimates a currency's 'fair-value' based on its crossborder flows of money and its balance of imports and exports - all of which go together to make up what economists call the 'Current Account'.

The current account is another factor, like interest rates, in the valuation of a currency, although it is seen as being a more background driver of a currency's value.

It is based on the idea that the balance of money flowing in and out of a country via exports, imports, cash transfers, repatriated savings, sales, and purchases of financial assets and myriad other assorted minor flows, combined suggest the net demand on a currency.

If a country's exports are high, for example, foreign buyers will need more of that country's currency to buy its exports leading to higher demand and the currency rising in value.

The model used by UBS uses this method to estimate the fair value of a currency, which in the case of the Euro appears to be 19% higher than the Euro currently trades at (versus a trade-weighted basket of other currencies).

The wide divergence between the model's fair value and the market value of the Euro suggests the Euro is unfairly undervalued and should rise in the future.

Accordingly, Farmakis is bullish for the Euro which he sees as one of the most undervalued currencies in the G10.

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider by getting closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank for international payments. Learn more here.