Central Banks Could Be Making Another Mistake and Yet Cause an Economic and Financial Collapse

- Written by: Gary Howes

-

Image © Adobe Stock

The current "shocking decline in the money supply" is being ignored by central bankers, and this could yet result in "financial collapse" warns Albert Edwards, Co-head of Global Strategy at Société Générale.

The assessment by Edwards comes as central banks across the world race to raise interest rates with both the Bank of England and Norges Bank surprising on Thursday, June 22 by raising the tempo of their respective cycles with 50bp hikes.

This month also saw the Reserve Bank of Australia end its hiatus from hiking, as did the Bank of Canada.

The European Central Bank is not done and all signs point to another hike from the Federal Reserve in July.

Edwards says these late-cycle interest rate hikes could prove to be a mistake in the same vein as these same central bankers made mistakes when dismissing the prospect of a surge in inflation that has subsequently proved unwilling to fall back.

For Edwards, the mistake comes down to watching the money supply in the economy.

"When I started work in financial markets in 1982, monetarists were considered to have won the economics argument. Yet for the last few decades they have been pushed to the edge of the economics world, excluded and often ridiculed by the mainstream. Central bankers, including Fed Governor Jay Powell have explicitly stated that they no longer look at money supply," he explains, adding:

"So, it is no surprise that just as the monetarists who accurately called the current inflation take-off were ignored, the current shocking decline in the money supply is also being ignored. This could prove to be a mistake of the highest order as ‘higher for longer’ may yet cause a surprise economic and financial collapse."

Monetarism is a school of thought in economics that maintains the money supply (the total amount of money, and velocity of money, in an economy) is the chief determinant of economic growth in the short run and inflation over longer periods. It is a school of thought that gained prominence in the 1970s—bringing down inflation in the United States and United Kingdom.

"I remember as a high school student around 1977, happily sitting in The Plough pub near my home in Kew Gardens, London reading Milton Friedman’s pamphlet on the expectations-augmented Phillips Curve. This showed there was no trade-off between unemployment and inflation because the long-run Phillips curve was vertical. By the time I started working in finance a few years later, the weekly US money supply data had become the most important data point on an economist's schedule," says Edwards.

He says the June release of inflation data in the UK "sent a shiver of fear across central banks" as it suggested inflation risked becoming embedded.

"There is no doubt in my mind that central bankers are primarily responsible for the mess we now find ourselves in, having monetised away huge pandemic-era fiscal deficits at a time of severe supply constraints," says Edwards.

In short, central banks must answer for their policies of ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing to fund the significant government giveaways of the pandemic era.

These giveaways bloated savings accounts which has continued to fuel demand in a deglobalising world that means the supply of goods has become compromised.

"Central bankers became overconfident (aka smug), as they believed monetarists were proved wrong in warning that QE would cause inflation to take off in the wake of the 2008 GFC," says Edwards. "The explosive inflationary outturn was inevitable."

Looking ahead, Edwards is concerned monetarism is still being ignored.

He notes money supply in the U.S. is falling at the fastest rate since The Great Depression, meaning if monetarists are right "economic growth and inflation may soon collapse as central bankers make yet another huge policy error."

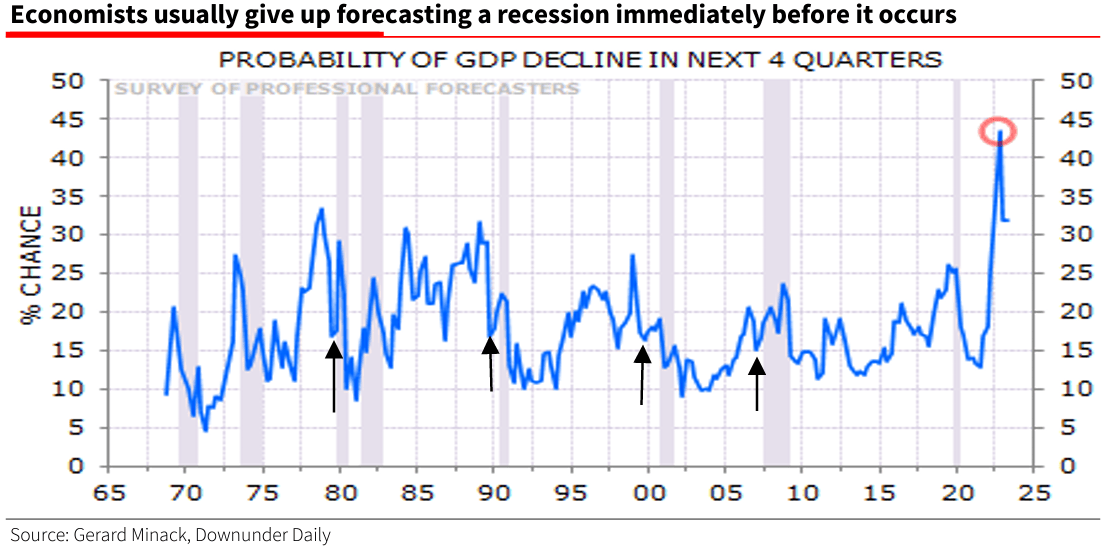

"It will also come as a big shock to investors who, as usual, are giving up on their forecasts of recession, just as one looms into view," he warns, citing evidence that "economists usually give up forecasting a recession immediately before it occurs."

In the Eurozone and UK, M2 growth (a measure of money supply) has slowed to historical lows and is barely positive on a year-on-year basis.

"In real terms the slump is unprecedented in recent times," says Edwards.

In a surprising turn of events, Edwards reveals he is not, in fact, a monetarist.

"Sometimes M2 growth merely tells us nothing more than interest rates have changed, and shifts have occurred between the various monetary aggregates. Hence, I often prefer to look at the counterparties of money supply to delve deeper into what is happening to bank lending," he says, but:

"Unfortunately, this too is sliding into unusual contraction, waving a big red cyclical warning flag."

He presents evidence that U.S. bank lending is now contracting on a 6-month basis, which he deems "highly unusual."

"Some sceptics still dismiss this data, arguing QT is draining treasuries from banks (excluding this, bank lending is still positive). We checked out the Fed’s H8 release and looking at the chart above I still get a very recessionary, if not depressionary sense. But hey, maybe this time is different?" concludes Edwards.