Bank of England Interest Rate Decision and Different Reasons on the MPC

- Written by: James Skinner

-

Image © Adobe Stock

The Bank of England (BoE) raised interest rates again this week but not all on the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) agreed with the decision due to a three-way split of views about how quickly inflation could be expected to fall.

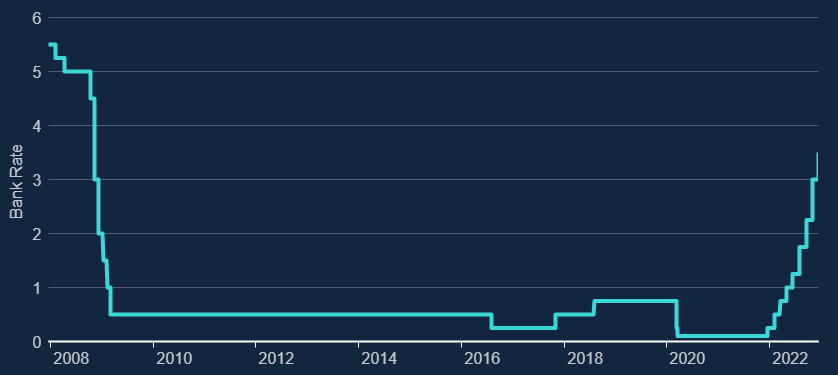

Bank Rate was lifted by half a percentage point to 3.5% on Thursday in what is the ninth increase since last December but only six members of the nine seat MPC supported the move while one member preferred a larger increase to 3.75% and two other members voted for no further increase at all.

The decision brings the 12-month increase to 340 basis points or 3.4% and makes for a stronger tightening of policy than in the last true cycle between July 2003 and July 2007 during which Bank Rate rose from 3.5% to 5.75%.

It leaves Bank Rate at nearly five times its typical level of the last five years, reflecting the largest increase since the period between May 1988 and October 1989 when the Minimum Band 1 Dealing Rate doubled from 7.37% to 14.87%.

"The labour market remained tight and there had been evidence of inflationary pressures in domestic prices and wages that could indicate greater persistence and thus justified a further forceful monetary policy response," the meeting record says of the majority on the committee.

"Although activity in the economy was clearly weakening, there were some signs that it was more resilient than had been expected and it was therefore uncertain how quickly the labour market would loosen. Other economic forecasters had also continued to predict a stronger outlook for demand," it adds.

For a majority on the MPC rising wage growth and low unemployment were driving services prices higher and posing upside risks to the BoE's forecast for inflation to fall rapidly in the years ahead, making those things prominent reasons for the BoE decision.

Office for National Statistics data had suggested earlier this week that inflation fell from 11.1% to 10.7% last month and that wages grew by an annualised 6.1% percent in the three months to the end of October once bonuses are included.

Wage costs do make up a substantial portion of overall costs within services-selling companies and the risk of increasing pay settlements leading to a self-sustaining cycle of inflation was cited by the sole voter on the MPC who preferred a larger increase in Bank Rate to 3.75%.

"Another more forceful monetary tightening now would reinforce the tightening cycle, importantly leaning against an inflation psychology that was embedding in wage settlements and inflation expectations, and was pushing up core services and other underlying inflation measures," the meeting record states.

"Pulling forward monetary action now would reduce the risk that Bank Rate would need to rise well into next year even as the economy slowed further," it adds after also noting that "greater evidence that price and wage pressures would stay strong for longer than had been projected in the November Report."

For others among the dissenters, the size of the increases announced so far and other recent data emerging from the economy were chief among reasons for voting to leave interest rates unchanged on Thursday.

"The real economy remained weak, as a result of falling real incomes and tighter financial conditions. There were increasing signs that the downturn was starting to affect the labour market," the meeting record notes.

"But the lags in the effects of monetary policy meant that sizeable impacts from past rate increases were still to come through. That implied the current setting of Bank Rate was more than sufficient to bring inflation back to target, before falling below target in the medium term. As the policy setting had become increasingly restrictive, there was no longer a strong case for further tightening on risk management grounds," the 'dovish' dissenters concluded.