Why the UK is the Straggler Among G7 Economies - Pantheon Macroeconomics

- Written by: James Skinner

-

"This is partly because consumer energy prices haven't risen much in the U.S. and have been controlled directly to a greater extent by Eurozone governments" - Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Image © David Holt, Accessed: Flikr, Licensing Conditions: Creative Commons

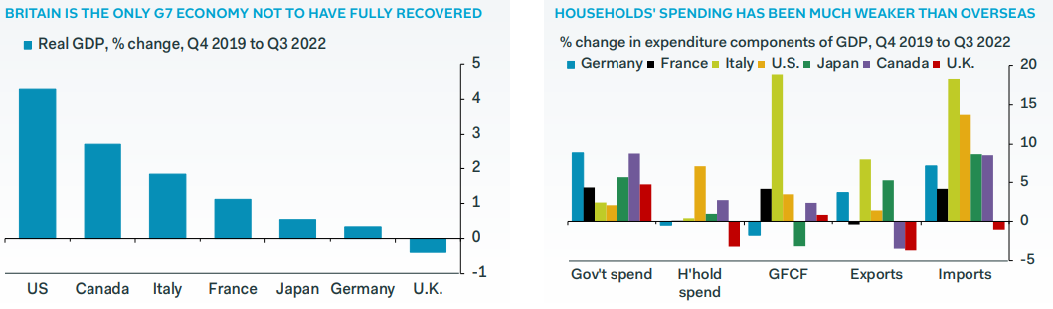

Recent data has shed fresh light on why the UK has emerged as the standout underperformer among G7 economies since the onset of the pandemic, according to Pantheon Macroeconomics, and slower growth in household spending accounts for much of the difference.

Britain's economy is yet to recover to its pre-coronavirus level of GDP while all other G7 economies are now larger than they had been at the end of the final quarter in 2019, leading to widespread speculation in recent months about what might have caused this underperformance.

But final estimates for third quarter growth in other G7 economies released over recent weeks contained the answer to this question.

"Relative weakness in households' real spending has been the main contributor," writes Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, in a Wednesday research briefing.

"Households' real spending was 3.2% lower in Q3 2022 than in Q4 2019, compared to an unweighted average increase across the other G7 economies of 1.8%," he adds.

Growth in household spending has not kept pace with rising prices, meaning it has declined in real terms and more so than anywhere else, making it a drag on GDP growth that tends to be measured in real or inflation-adjusted terms.

"This is partly because consumer energy prices haven't risen much in the U.S. and have been controlled directly to a greater extent by Eurozone governments," Tombs says.

"But note too that core goods prices have risen more in the U.K. than in the Eurozone since Brexit, whereas previously they moved in sync. This suggests British households have paid the price for the greater cost and complexity faced by overseas businesses exporting to Britain," he adds.

Energy price subsidies have been larger and more effective in the large Eurozone economies than they have in the UK where assistance is also set to be scaled down from next April in a policy change that will have further adverse implications for the economy and inflation.

High energy prices resulting from more limited government intervention than elsewhere have been a significant driver of the UK economic underperformance but the difference between employment levels in the UK and other G7 economies prior to the pandemic has also been relevant too.

"This is partly because the U.K. already was at full employment in 2019, whereas the Eurozone's labour market still had some slack," Tombs says.

"Some of the U.K.'s underperformance, therefore, reflects the fact that it already was running up against supply-side constraints before Covid, due to its decent growth over the course of the 2010s," Tombs says.

This contrasts with the situation in Europe where the unemployment rate was 7.4% in December 2019, almost twice the level of the 3.8% unemployment rate in the UK, while the fall to 6.5% in Eurozone unemployment has been larger than in the UK where unemployment has fallen to only 3.6% in the latest data.

But while differentials between employment and government energy subsidies have accounted for a large part of the yawning growth gap, other factors are also likely to contribute going forward including government belt tightening and Bank of England (BoE) interest rate policy.

"Indeed, U.K. households will be hit relatively hard by rising interest rates, due to the high rollover rate of mortgage debt, and they look set to endure a multi-year period of frozen income tax thresholds too. It is no wonder, then, that they are more downbeat than households in the U.S. and Eurozone," Tombs says.

"All told, the outlook for much tighter fiscal and monetary policy suggests Britain will fall further behind its peers in 2023. We look for a 1.5% year-over-year fall in U.K. GDP next year, compared to growth of 0.8% in the Eurozone and 1.0% in the U.S," he adds while writing in a Wednesday research briefing.