Bank of England Accused of Self-inflicted Confusion

- Written by: Gary Howes

-

Image © Pound Sterling Live

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand couldn't be clearer when they said this week they will hike rates rapidly to kill off any prospect of Kiwi inflation becoming self-sustaining.

The RBNZ raised interest rates by 50 basis points to 2.0% and said they will keep going until they were sure inflation was under control under their 'least regrets' framework.

But the same level of clarity and purpose is sorely missing at the Bank of England according to a new analysis from Berenberg Bank who say policy makers at Threadneedle Street are "failing the key test".

"The biggest surge in inflation in 40 years has put the Bank of England’s (BoE’s) monetary policy framework for price stability to the test. How well is it doing? Unfortunately, the evidence is not favourable," says Kallum Pickering, Senior Economist at Berenberg Bank.

The UK's current surge in inflation - it rose 9.0% in the year to April - undoubtedly has its roots in external sources that the Bank cannot influence, most notably surging energy costs.

But the key concern for central banks is whether or not this imported inflation starts to influence domestic inflation, most notably via pushing up wages and the prices business slap on their goods and services.

This 'unanchoring' or 'deanchoring' is typically addressed by higher central bank interest rates.

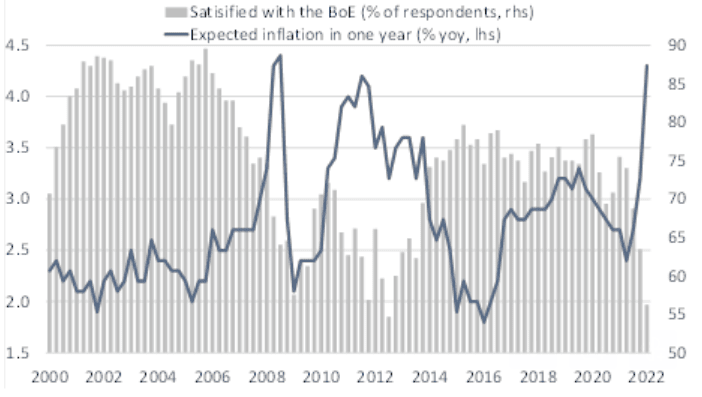

Berenberg Bank finds UK inflation expectations are now unanchored, despite efforts to contain them via tighter policy.

"Public perceptions of the BoE have plunged," says Pickering. "These failures come amid a major push since 2014 to improve policy outcomes by increasing openness and transparency".

Above: Bank of England inflation attitudes survey. Image courtesy of Berenberg.

Berenberg identify some key areas of failure at the Bank, including explicit forward guidance (started in 2013) and "the huge increase in information published by the BoE alongside policy decisions".

They also assess the Bank's forecasts and argue that the decision to produce multiple projections distorts, rather than strengthens, policy signals.

Indeed, the team at Pound Sterling Live spend hours poring over a series of complex charts and tables on the occasion of the Bank's quarterly Monetary Inflation Reports, deliberating over what they actually mean and where the emphasis lies.

"A well-designed framework should preserve credibility when the economy is hit by unexpected shocks. Instead, we think that recent events have demonstrated that the BoE’s overly complex framework – designed during an era of low and stable inflation – is not fit for a world of high and uncertain inflation," says Pickering.

On the whole, the Bank is accused by Berenberg of reacting too late to an inflation problem that it still does not fully understand.

"But instead of providing clarity about how it may react in case of future inflation surprises, its overly complex approach to forecasting and communication blurs the bank’s reaction function, adds to economic uncertainty and undermines credibility," says Pickering.

Indeed, the Pound fell sharply following the May Monetary Policy Report where the Bank simultaneously hiked inflation forecasts but pushed back against the market's expectations for the number of incoming rate hikes.

Their argument against a RBNZ-style series of rapid and confident hikes was that it would slow growth towards recessionary levels.

Yet the Bank leads every policy meeting and MPR text with the statement their number one objective is to guarantee price stability by keeping inflation anchored to the 2.0% policy target.

This is however mere lip service if growth concerns are proving the overarching determinant of policy guidance.

"Unless the BoE opts for a leaner and more pointed communication strategy, financial and economic actors will continue to struggle to understand the BoE’s reaction function or predict what the bank may do next, in our view," says Pickering.

"In turn, inflation expectations are likely to remain unanchored for longer, that is until price pressures begin to ease on a sustained basis due to positive global supply developments or until the BoE produces disinflation by raising interest rates well above their neutral rate – which would probably tip the UK into a recession," he adds.